Closing speech of the Public Prosecution Service day 2 (21 December 2021)

On Monday 20 December, Tuesday 21 December and Wednesday 22 December 2021 the Public Prosecution Service presented its closing arguments in the MH17 case. For the presentation on day 2 please read the text below or watch the video (in Dutch with English interpreter).

3.5 Downing of flight MH17 with the Buk TELAR

3.5.1 Introduction

And so, at the instruction and under the supervision of the four defendants, the Buk TELAR was transported to the launch location in the vicinity of Pervomaiskyi. At this point, the wiretap on Kharchenko’s number went silent. Kharchenko could no longer be heard on intercepted calls after 14:10; Pulatov went silent after 13:36. Historical telecom traffic data for the number ending in -511 showed that on 17 July 2014 from 15:48 until 16:31 it was transmitting to phone masts in Pervomaiske, close by Pervomaiskyi. But no conversations were intercepted, so further more: radio silence. Nevertheless, the investigation did produce a great deal of information about what occurred at this location.

3.5.2 Firing of the Buk missile

For example, eye witnesses reported seeing a missile launch in this location on 17 July 2014, and photos showed a missile smoke trail, while satellite photos revealed traces of the launch.

3.5.2.1 Witnesses at the launch location

Two witnesses saw a Buk missile launched from the agricultural field at Pervomaiskyi: X48 and M58.

3.5.2.1.1 Witness X48

Witness X48 was positioned at a DPR checkpoint (‘blockade point’) on the through road from Snizhne to Saur-Mogila. There are fields and rows of trees across this landscape. When he was examined by the examining magistrate the witness marked this location on a map.

He saw a dark green Buk driving, and five or six minutes later heard an explosion. Above his head a missile trail appeared, and he then heard a second explosion in the air. He saw pieces of an aircraft falling to the ground in a fan shape. The Buk then drove to the road. It was now missing one of its missiles. X48 also described four soldiers who caught his attention. They looked different from the soldiers at the checkpoint, and wore helmets with ‘ears’. Investigation revealed that within a TELAR the crew communicates using a ‘tank helmet’, a protective helmet with covered earphones and an audio link. After the aircraft wreckage hit the ground, these four soldiers moved off in the direction of the checkpoint. The witness saw the launch location burning and later being ploughed over by a tractor.

3.5.2.1.2 Witness M58

Witness M58 was also present at this location. He stated that the day before the disaster involving the Boeing, he and other volunteers from Marinovka were taken to a crossroads south of Snizhne in order to repel a breakthrough by Ukrainian fighters. This was a crossing of a paved road with an unpaved road. At the crossroads, witness M58 saw a checkpoint (‘a block point’), trees, fields with crops including wheat, and (in the distance) hills. The checkpoint was located on the paved road. After he arrived the witness helped to set up one or two tents, and he dug trenches. The next day the witness saw and heard a vehicle pass by, which he later recognised as a Buk TELAR. Shortly thereafter, he heard an explosion and saw a missile shoot into the sky in the direction of a large aircraft. He saw that the missile left a trail behind it, like you would see behind an aircraft. The witness stated that the aircraft was hit and then fell to the ground. He continued watching as the plane fell as smoke accumulated. He saw the Buk TELAR standing in the field, and later saw it at the crossroads. At that point he saw that one of its missiles was missing. He believes he also saw painted-over digits on the left side of the TELAR, one of which he thinks had been a ‘2’. After the downing of the aircraft, there were several fighters at the crossroads. On various occasions the witness marked the spot where he saw the Buk TELAR standing in the field. This point varies from closer to the crossroads to a little further from these crossroads, close by the point identified by X48.

Speaking in 2019 about the reaction to the downing of the aircraft, witness M58 told the examining magistrate the following:

‘We were really happy, because they told us that a military transport aircraft had been hit. That’s what everyone said, including the commanders. (...) I also spoke to someone who was their commander, a well-built fellow, someone local, a Ukrainian. He said: we’re heading to the spot where the plane crashed, and like us he was happy. They drove away. (…) About an hour later, or maybe a bit more, they returned, looking really sombre. I asked: what’s going on? He said: it isn’t a military aircraft. He said: There are all these...’

Witness M58 was in tears before the examining magistrate as he finished his sentence:

‘He said, there are all these children’s toys lying around.’

In late 2020, too, the witness became emotional when he concluded his four-day examination by expressing his sympathy for all the victims and next of kin.

The testimony of witnesses X48 and M58 about the missile launch at the location in question is supported by various statements given by witnesses in the area, by photos of the smoke trail coming from the location described by X48 and M58, by satellite images and – as regards the deployment of a Buk missile – the results of the forensic investigation.

3.5.2.2 Other witnesses to the flight of a missile

At the time of the missile launch, flight MH17 was flying at an altitude of around 10 km and around 34 km to the northwest of the location identified by witnesses X48 and M58. Around 32 seconds elapsed between the moment the missile was launched and the moment it hit MH17.

A large number of witnesses gave statements about a missile launch in the vicinity of Snizhne, Torez and Pervomaiskyi.

Twelve of these witnesses mentioned a smoke trail in this connection. Eleven witnesses who mentioned an explosion or smoke trail also mentioned a Buk installation they had either seen earlier that day or had heard about. And in regard to the appearance of the smoke trail, a number of witnesses specifically mentioned the hill, Saur Mogila, to the south of Snizhne, as well as the towns of Pervomaiskyi and Pervomaiske. These statements do not in themselves provide evidence of the launch location, but they correspond closely to the statements given by witnesses X48 and M58.

3.5.2.3 Photos of smoke trail

At 16:20 a resident of Torez, whose name is mentioned in the file, heard two heavy explosions within a short period of time. The second explosion was much louder than the first; so loud, in fact, that it made the window panes shake. This resident grabbed his Nikon camera and went to the balcony of his apartment, where he saw a trail of smoke coming from an object he did not recognise. The trail rose directly over his home. At 16:25 he took two photos of this trail. One of these photos, together with a version of the same photo whose contrast has been adjusted by the KNMI, is shown here.

3.5.2.3.1 Metadata

The photographer made his camera and memory card available for investigative purposes. Analysis of the metadata showed that the photos of the smoke trail were taken at 16:25:41 and 16:25:48.

3.5.2.3.2 NFI investigation into photos’ authenticity

The NFI examined the camera and memory card and no indications that the image had been manipulated were found. The NFI further concluded that the photo files were in consecutive order and that the metadata saved in the NEF files indicated the use of a Nikon camera. The same type of camera that the photographer provided and that he said he had used to take the photos.

3.5.2.3.3 KNMI investigation into smoke trail\

In addition, the KNMI examined the image of the white smoke trail on one of the two photos. Since the trail is clearly vertically oriented and is thickest at the horizon, the KNMI ruled out the possibility that the trail originated from an aircraft at high altitude. The KNMI further concluded that the cloud pattern on the photo was consistent with the cloud visible on satellite images on the afternoon of 17 July 2014.

3.5.2.3.4 Investigation into origin of smoke trail

The KNMI also investigated the direction of the smoke trail. On the basis of the landmarks visible on the photo and the coordinates of the photographer’s location, the KNMI was able to establish the orientation of these photos. The same research was also performed by a private blogger, the investigative collective Bellingcat and the investigation team itself. All this research led to the conclusion that the photos of the smoke trail were taken from a south-easterly direction from a flat north of Torez, and that the path of the smoke trail was consistent with a missile launch in the agricultural field near Pervomaiskyi.

3.5.2.4 Satellite images of marks in agricultural field

It also follows from satellite images of the agricultural field near Pervomaiskyi that the missile was fired from this location.

3.5.2.4.1 Scorch marks

When a Buk missile is being launched, the soil on which the TELAR is standing could catch fire. In satellite images taken on 20 and 21 July 2014, the northwestern corner of this field was black. This was not the case in the satellite photo of 16 July 2014. A dark line is visible on the black part of the field. According to an image analyst from the Ministry of Defence, this dark line was a consequence of the ground being ploughed. This is consistent with the statement by witness X48 that the place where the missile was launched caught fire and was later ploughed over by a tractor. The European Space Agency (ESA) also assessed the satellite images. According to ESA the visible change in the northwestern corner of the field was consistent with the effects of fire. Furthermore, in principle ESA saw no reason why a farmer would burn or plough the field in such an uneven manner. ESA could find no examples of the field being worked in such an uneven manner in older satellite images of the field. ESA therefore concluded that an abnormal occurrence had taken place in the northwestern corner of the field between 16 July and 21 July 2014, causing significant damage to the ground, including fire. This is consistent with a missile launch.

3.5.2.4.2 Fire’s point of origin

Working on the hypothesis that the black mark in the field was a burn mark, the KNMI investigated where the fire’s point of origin was and how the fire had spread from there.

The KNMI observed that at 16:20 (UTC+3) on 17 July 2014 there was a northeasterly to easterly wind in the region. If a fire originates in one spot, its seat will move with the wind, which may make the seat wider. This means that a fire burning in a northeasterly to easterly wind could expand in a southwesterly to westerly direction. If the fire started at around 16:20 on 17 July 2014, then of the locations supplied by the police only location B (or somewhere in the vicinity of location B) is a logical point of origin. Location B is the place where, according to X48, the missile was launched.

3.5.2.4.3 Tread marks

Besides showing a burn mark, the satellite images of 20 and 21 July also show tread marks that do not appear on the satellite photo of 16 July 2014. The most striking tread mark can be seen at the spot identified by X48 as the launch location.

This mark is over three metres wide and runs from the edge of the woods a short way into the field. The chassis of a TELAR is 3.25 m wide. According to the aforementioned image analyst from the Ministry of Defence, the track appears to be too wide for a mowing machine and is more consistent with a vehicle on caterpillar treads that drove into the field from the woods and then returned via the same track.

Witness M58 stated that he heard the TELAR driving alongside the trees on the northern side of the field prior to the missile launch, that the TELAR remained beneath the shadow of the trees after the missile was launched, and that it then drove to the crossroads.

The satellite image of 20 July 2014 also showed marks at the crossroads which are absent on the image of 16 July 2014. The Ministry of Defence image analyst identified possible tread marks that approached the crossroads from the north and turned in a large arc towards the launch location. These tracks therefore run from the paved road to the unpaved road, or vice versa. These track marks dovetail precisely with M58’s statement.

3.5.2.4.4 Tents

As mentioned previously, M58 also stated that the day before the downing of flight MH17 he had set up one or two tents in the vicinity of the crossroads. On the map he drew these in the upper left corner of the crossroads.

On 9 February 2019 M58 sent the investigation team a photo of a similar tent with the comment: ‘We had two tents like this at the checkpoint!’ The tent in question was a circular, light-coloured army tent. In exactly the same location as where M58 had drawn two tents, the satellite photos of 20 and 21 July 2014 show two white, circular spots which were not visible on the image of 16 July 2014. Although the presence of tents says nothing about whether or not a missile was launched, this finding is relevant to the assessment of the reliability of M58’s statement.

3.5.2.5 Video of and witness to mark in agricultural field.

In addition to satellite images of this location we also possess video images filmed by a British journalist.

On 22 July 2014 this journalist travelled with a colleague to an area south of Snizhne, in search of a launch location. In a grain field they ask the driver of a combine harvester whether he has seen a missile launch installation. The farmer points them in the direction of a piece of land a short distance further, which according to him has been burned. In this agricultural field the journalist sees that the grain is scorched. It is, he says, as if there has been a fire blast causing the crop to burst into flame. They film the location and then drive on further on an unpaved rural road. Further up the road they come to a rebel-controlled checkpoint concealed in the trees. It is positioned by a crossroads and, according to the journalist, looks as if it is a permanent checkpoint. The journalist mentions the coordinates where he saw the ‘burn mark in the field’. This spot is located in the top-left corner of the field that X48 and M58 mentioned in their statements and which can be seen in the satellite images 20 and 21 July 2014, though not in the image of 16 July. The location of the checkpoint mentioned by the journalist is also consistent with the statements of witnesses X48 and M58.

3.5.2.6 Sub-conclusion

We will now summarise the foregoing. If we trace the route of the Buk TELAR convoy and listen to the intercepted phone conversations about its destination, we end up in an agricultural field nearby Pervomaiskyi. Various witnesses saw that the Buk TELAR did actually fire a missile from there on the afternoon of 17 July 2014. First and foremost, X48 and M58 were present at the launch location that very afternoon. In addition, many other witnesses saw a missile, or something that looked like a missile, in flight. One of them took two photos of it, showing a vertical smoke trail that could not be from an aircraft and that was travelling from the direction of the same field near Pervomaiskyi that X48 and M58 spoke about in their statements. The TELAR and the Buk missile left traces behind – burn marks and tread marks – which can be seen on satellite photos and a video. Those traces correspond to what witnesses X48 and M58 observed in that field.

3.5.3 MH17 was hit by a Buk missile

It is clear from the forensic evidence that MH17 was subsequently hit by this Buk missile. During the consideration of the merits of the case, the court paid close attention to the forensic investigation. We will now discuss the key results that unmistakably indicate the use of a Buk missile.

3.5.3.1 General damage pattern

First of all, this is the pattern of damage observed on the wreckage of MH17, and more specifically the hundreds of small and larger perforations, dents, damage caused by a glancing impact and soot marks concentrated on the left and upper sides of the cockpit. This damage pattern was not found on the right side of the aircraft. The concentration of the damage on the left side visibly decreases towards the rear. According to experts from the Russian firm Almaz-Antey (AA), the Netherlands Aerospace Centre (NLR) and the Belgian Royal Military Academy (RMA), this damage pattern is consistent with the use of a Buk missile.

Research by the NFI concluded that most of the dents and perforations were the result of impacts by steel objects. A Buk missile warhead contains pre-formed steel fragments. Further research showed that the elemental composition of the steel fragments found in the dents and perforations was consistent with that of the pre-formed fragments from a Buk missile warhead.

3.5.3.2 Metal fragments

Secondly, we would draw the court’s attention to the metal fragments found in victims’ bodies, flight documents and wreckage.

3.5.3.2.1 Metal fragments in bodies, flight documents and wreckage

A total of 370 fragments were found in victims’ bodies, flight documents and wreckage.

The NFI selected a number of these for further investigation. These fragments were then compared with fragments from six 9N314M warheads, including fragments secured after the arena tests in Ukraine and Finland. A total of 195 fragments were examined.

The NFI concluded that:

- all the fragments examined were made of unalloyed steel and had an elemental composition consisting of iron with traces of silicon, chromium, manganese and copper;

- all of these fragments were produced by cutting, sawing or chopping hot-rolled low-carbon ferritic steel bars. They were then sandblasted and rinsed or otherwise treated with phosphoric and/or sulphuric acid;

- all of the fragments examined have a microstructure that is largely determined by compression of the steel during the explosion, on impact with the aircraft and through heating around the edges during the explosion and impact.

In other words, all of the fragments examined are consistent in terms of their elemental composition, production process and microstructure.

3.5.3.2.2 Bowtie- and tile-shaped fragments in bodies of crew members

The NFI also concluded that the fragments examined had three distinct shapes: bowties, tiles and rectangles. On the basis of NFI forensic photos and microCT images, two of the fragments examined by the NFI are clearly recognisable as being bowtie- and tile-shaped, even to a layperson. We can see this right now.

The Russian Federation and Almaz Antey provided information on the shape and dimensions of the fragments from the 9N314M warhead: the dimension of the bowtie is 13X13X8,2 mm, the dimension of the square is 8X8X5 mm and the dimension of the filler is 6X6X8,2 mm. These dimensions are virtually the same as those of the fragments secured after the dismantling of a 9N314M warhead in Ukraine, as established by the JIT. The forensic photos with the ruler we have just exhibited show that the bowtie and tile fragments found at the crash site have the same dimensions as the same-shaped fragments from the 9N314M warhead of a Buk missile. They also resemble the bowties and tiles secured after the arena tests in Finland and Ukraine.

These two fragments were found in the bodies of two crew members:

i. the bowtie in the body of the captain of team A;

ii. the tile in the body of the first officer of team A.

Layers of melted cockpit glass were found on these two fragments. According to the NFI, this can only be explained by the fact that the fragments came from outside the aircraft.

The Buk TELAR that we see on the films of 17 July 2014 can launch three types of Buk missiles: the 9M38, the 9M38M1 and the 9M317. These missiles are equipped as standard with their own warhead: the 9N314, the 9N314M and the 9N318, respectively. Although developed for the 9M38M1 missile, the 9N314M warhead also fits on a 9M38 missile. This was established during the dismantling of a 9M38 missile and was confirmed by the experts from Almaz-Antey and the RMA when they were examined by the examining magistrate.

According to Almaz-Antey, the shapes and dimensions of the fragments are specific to each type of warhead. The bowtie, for example, is only found in the 9N314M warhead. According to the RMA’s expert, too, the bowtie fragments are unique to the 9N314M warhead of a Buk missile.

3.5.3.3 Other missile parts

Besides metal fragments, materials from a source other than the aircraft and consistent with a Buk missile were found lodged in the wreckage of MH17.

A foreign object in the form of a piece of stainless steel was found in part of the aircraft’s metal frame on the left side of the cockpit (AAGK3338NL). A twisted piece of dark green metal was found in the groove of the frame of the left cockpit window (AAHZ3650NL). Both objects were embedded in the aircraft wreckage. In the case file they are also referred to as the ‘lump’ (from the aircraft’s frame) and the ‘green lump’ (from the window frame groove). The NFI removed these objects from the wreckage. The lump from the frame was then sawn into three pieces. All parts were subsequently examined by the NFI and by forensic specialists from the Australian Federal Police (AFP). We will first discuss the NFI investigation.

3.5.3.3.1 Elemental composition and microstructure

The NFI determined the elemental composition and microstructure of these fragments. Both consisted of hot-rolled martensitic stainless steel. The NFI also determined the elemental composition and microstructure of various parts from several reference Buk missiles, such as the umbilical base plate and umbilical slide cover. These slide covers and base plates are located on a contact point in the tail section of a Buk missile to which the cable of the Buk launch vehicle is connected. On the basis of their elemental composition and microstructure, the object from the aircraft’s frame and the object from the cockpit window frame groove cannot be distinguished from material in the slide covers and umbilical base plates of the 9M38 reference missiles and one of the two 9M38M1 reference missiles. In other words, according to the NFI these objects must have been produced using the same material as the slide covers and umbilical base plates of these reference missiles. These are either from the same stainless steel plate or from multiple plates that are identical on the basis of their composition. In these types of investigations the NFI often uses a number of hypotheses. The results of the investigation are then used to determine the probability or improbability of a particular hypothesis. In this case, according to the NFI the findings are much more likely (i.e. much more explicable) if these fragments came from the slide cover and umbilical base plate of a Buk missile than if they came from a different source, such as another weapon.

3.5.3.3.2 Other physical characteristics

As well as the NFI’s comparison on the basis of elemental composition and microstructure, the AFP physically compared these stainless steel objects from the aircraft’s frame and window frame groove with the slide cover and umbilical base plate of a Buk missile. We will now explain how the AFP has conducted this investigation and will show this with images of the green lump from the cockpit window frame.

Firstly the AFP measured and described, noting the weight, shape, colour and dimensions of this green lump. Then it was noted that it is magnetic. Furthermore it was discovered that this lump has torn edges, exhibits signs of machine tooling, and has smooth surfaces, a machined hole and ‘folded’ edges.

There is in any case a green milled plate, and underneath it a silver-coloured plate with holes. This green plate has a pre-formed edge and is approximately 1.8mm thick. The sides of this edge appear to have been rounded off by hand. Two parallel stripes can be seen on the surface, with a space of around 25mm between them, and positioned perpendicular to the pre-formed edge. There are also arc-shaped milling marks visible, running in the same direction as the parallel stripes. The back of this piece is not painted and appears smooth.

In the silver-coloured plate there is a hole with a diameter of approximately 6mm. The edge of the hole is around 3.4mm from the pre-formed plate edge. Fine stripes are visible on the plate. After its examination the AFP concluded that the green and silver-coloured plate formed a single whole.

In total the AFP established 32 points on the basis of which the metal lump could be compared to the reference material, consisting of the umbilical base plate of a 9M38 and a 9M38M1 missile.

When examining this reference material it is immediately noticeable that one side of both base plates is green and the other side silver-coloured. It is also noteworthy that the plates have been milled in a certain way and contain holes. We will show these milling marks later. The base plates also have a guide rail on both sides.

This guide rail allows the slide cover to move back and forth. After the AFP had provided an in-depth description of the umbilical base plates, it went on to compare them with the green metal lump. The similarities observed were described in detail and shown in comparison charts. We will show a few of those again now.

Here on the left we see part of the green plate and on the right part of the umbilical base plate of the 9M38 reference missile. On both parts several arc-shaped milling marks (#4, #7 and #8) can be seen side by side. They all have the same width and they all form the same fan-shaped pattern. The previously mentioned stripes (#5 and #6) can be seen on either side of the milling marks.

On the following comparison chart we can see the pre-formed edge (#9) of the green plate and the pre-formed edge of the reference material. The sides of both edges (#3 and #17) appear to have been rounded off by hand and match in terms of thickness.

Here on this comparison chart on the left we see the silver-coloured plate of the metal lump and on the right part of the umbilical base plate of one of the reference missiles. A machined hole can be seen in both plates. They are positioned the same distance from the pre-formed edge (#14). On the next chart, once more we see the whole (#10) but we also see the same type of milling marks (#32) on both plates.

And on the last comparison chart here (44) the end of the guide rail (#19) can be clearly seen on both parts.

To the left of this is the pre-formed hole (#10), which in this photo of the reference material is only visible as a light mark but which is clearly visible if viewed in person. It was described by the reporting officer. The pre-formed edge (#14 with the rounded off sides (#15, #16 and #23) can also be seen.

As regards the green and silver-coloured plate from the metal lump from the window frame groove, the AFP concluded that these originally formed a single whole and that the external characteristics of this lump match a specific part of the umbilical base plate of both the 9M38 and the 9M38M1 reference missiles.

The AFP did the same with other retrieved missile parts, including the aforementioned metal lump from the aircraft frame, which was cut in three parts. On the basis of this comparative analysis the AFP concluded that the external characteristics of the three parts of the metal lump recovered from the aircraft’s frame are consistent with a specific part of the slide cover of both the 9M38 and the 9M38M1 reference missiles.

3.5.3.3.3 Summary of other missile parts

In summary, the following was established with respect to these two foreign objects, i.e. the lump recovered from the aircraft’s frame and the lump recovered from the window frame groove. Both objects were embedded in the wreckage. In both cases the wreckage had to be sawed in order to remove the metal lumps. The NFI established the elemental composition and microstructure of both objects. These are consistent with the elemental composition and microstructure of the umbilical base plate and slide cover of the 9M38 and 9M38M1 missiles. The AFP determined the external characteristics of these metal lumps and compared them with those of the umbilical base plate and slide cover of the reference missiles. It concluded that there are a great many similarities. The metal lump in the aircraft’s frame was recognised as part of a slide cover and the lump in the window frame groove as part of an umbilical base plate.

The distortion of these two lumps and the manner in which they were embedded in the wreckage also convinced the RMA expert that their presence in the wreckage was the result of an explosion. They could not have been embedded into the wreckage in a static manner. Furthermore, according to the RMA these objects are unique to a Buk missile.

3.5.3.4 Sub-conclusion

From a forensic perspective, the circle is thus complete: the damage pattern made up of hundreds of small and larger perforations and dents is consistent with the detonation of a Buk missile warhead in the vicinity of MH17. Traces of steel in those perforations and dents have the same elemental composition as the fragments from a Buk missile warhead. In the wreckage of MH17 and in victims’ bodies steel fragments were found that in terms of their elemental composition, microstructure and production process are consistent with the fragments from a Buk missile warhead. Cockpit glass was found on some of those fragments. Fragments were found in the bodies of the captain and first officer that were bowtie- and tile-shaped, as established by the NFI. According to Almaz-Antey, bowtie-shaped fragments are only found in 9N314M warheads. This has been confirmed by the RMA and NLR experts. All the experts have further stated that a 9N314M warhead fits on both the 9M38 and 9M38M missiles. Parts from these types of missiles were found embedded in the wreckage of MH17. On the basis of these findings and the forensic investigation there can be only one conclusion: flight MH17 was downed by a Buk missile.

3.5.4 Conclusion

To summarise once more: the Buk TELAR was transported to the launch location near Pervomaiskyi at the instruction of and under the supervision of the defendants. This follows from the route taken by the convoy, which can be reconstructed in detail on the basis of mobile phone mast data, witness statements, social media posts and videos and photos of the Buk TELAR. It also follows from intercepted conversations in which Pervomaiskyi is mentioned as the final destination. Shortly before 14:07 the Buk TELAR reached its destination.

Two eye witnesses then saw the Buk TELAR fire a missile from an agricultural field near Pervomaiskyi, and various other witnesses in the vicinity observed the Buk missile in flight. One of those witnesses also took photos of the vertical smoke trail left by the missile, coming from the direction of the agricultural field near Pervomaiskyi. In the same field various traces were found: scorch marks from the ignition of the missile and tread marks from the Buk TELAR. Also traced afterwards was the checkpoint mentioned earlier that afternoon (at 13:09:27) by a subordinate of Kharchenko as a point of orientation for the final destination of the Buk TELAR and which was seen near the launch location by both eyewitnesses.

Finally, the fact that MH17 was indeed hit by a Buk missile is evidenced by the findings of the forensic investigation. In short: the damage pattern on the left and upper sides points to the detonation of a Buk missile warhead. Hundreds of fragments from a source other than the aircraft itself were found in the wreckage of MH17, flight documents and victims’ bodies. These fragments each have specific similarities with various parts of a Buk missile or a 9N314M warhead. Investigators found no evidence of a different weapon having been used.

The Public Prosecution Service therefore concludes that on 17 July 2014 flight MH17 was downed by a Buk missile launched from a Buk TELAR in an agricultural field near Pervomaiskyi.

3.6 Reactions to the downing of MH17

3.6.1 Introduction

The launch of the Buk-missile and the downing of MH17 produces many reactions that day. The defendants and other fighters discussed the incident primarily by phone. Local residents and journalists reported on it via social and other media. We will now take a general look at these reactions, because they tell a story about the involvement of the DPR in general and the involvement of the defendants in particular.

3.6.2 Reports of an aircraft being shot down

As early as 16:21, one minute after MH17 was downed, various social media posts mentioned the crash or downing of an aircraft near Snizhne and Torez. At the same time, in the first 20 minutes after the disaster various phone calls took place among DPR fighters in which they discussed the fact that they had downed an aircraft. Local residents also talked on the Zello app about an aircraft being shot down. Various types of military aircraft that had allegedly been downed were mentioned in the intercepted calls and Zello chats.

A short time later, at 16:37 the following message was posted on the VK account strelkov_info: ‘A message from the people’s army. An An-26 was just downed in the vicinity of Snizhne. It lies scattered on the ground behind the “Progress” mine.’

This post was later amended, with the sentence about the downing of an An-26 in the vicinity of Snizhne being deleted. Defendant Girkin stated that the messages had not been posted by him, and this was also emphasised on the VK account itself. However, this does not make these messages any less relevant. Indeed, it is relevant that immediately after the downing of MH17 the DPR claimed that an aircraft had been shot down from the area around Snizhne. Later, on 6 February 2015, this was again confirmed by defendant Girkin during a Russian witness examination. He stated that on 17 July 2014 at around 16:30 Moscow time he had received a report that an Su-25 belonging to the Ukrainian air force had been downed near Snizhne by ‘the air defence’. We will return to this statement later when we discuss the various standpoints of the defendants.

The fact that the DPR actively communicated about having downed an aircraft was confirmed by a French photographer in the area. In a video statement posted online he explains that he was called by the DPR press officer, who said: ‘We shot down a military plane from Ukraine’. He interpretes this as an invitation to report on the incident and goes to the crash site. On his way there, he receives information that it concerns a civilian aircraft from Malaysian Airlines.

3.6.3 Intercepted conversations about the Buk and downing of a Sushka

The first intercepted conversation after the downing of MH17 in which the defendants took part was at 16:48. This was less than 30 minutes after the incident. In this conversation Kharchenko tells Dubinskiy that they are ‘on the spot’ and have already downed a ‘Sushka’, a nickname for a Sukhoi combat aircraft. Dubinskiy says they have done well. Dubinskiy also tells Kharchenko to come to him but to leave one company behind to guard the ‘Buk’. About thirty minutes later, Dubinskiy checks with Kharchenko whether the ‘Buk’ has been positioned so as to prevent it from coming under artillery fire.

Meanwhile, various other phone conversations were taking place between DPR fighters in which the downing of an aircraft was discussed. In some of these conversations, people were already saying that there were probably civilians on board the aircraft. At 17:42 Dubinskiy was called by the DPR fighter with the call sign ‘Botsman’. Botsman says that an aircraft has been downed near him and that he is going to get the black boxes. Dubinskiy says that they have also shot down an aircraft – a Sushka – over Saur-Mogila and that they have a ‘Buk-M’. Later in the conversation Dubinskiy says that they downed two Sushkas the day before and another one that day. Thank God the Buk-M came this morning, Dubinskiy says.

3.6.4 Intercepted conversations about the downing of a passenger aircraft

Not long after this, the defendants started to realise that they had not shot down a Sushka but rather a passenger aircraft. At 18:20 Dubinskiy called someone going by the name of Igor. Igor says that journalists are hassling him and telling him that a Boeing has crashed 80 kilometres from Donetsk. He asks Dubinskiy if it is true that a Boeing has crashed. Dubinskiy appears not to understand, to which Igor says: ‘Boeing. The plane crashed.’ Dubinskiy then says, ‘Ah, well, our guys brought it down at Saur-Mohyla, there, near Marynivka.’ Igor corrects him and says: ‘That was Sushka, Sushka’, which Dubinskiy confirms, saying: ‘Our guys brought down the Sushka.’ Dubinskiy also says that he has heard that another aircraft has crashed, but that he doesn’t know anything about it. It therefore appears that they believed that two aircraft had been downed: a Boeing and a Sushka.

Around 7.30 PM Girkin’s assistant was called by DPR fighter Anosov, who said he had a message for Girkin. News broadcaster Russia24 has called him and said that the downed aircraft was a Boeing. According to Anosov, the Ukrainians downed the Boeing. They (presumably referring to Russia24) want to be the first to broadcast the news that the Ukrainians have downed a passenger aircraft so that they can blame the militia. Three minutes after this conversation, , Dubinskiy is called by the same assistant working for Girkin. He tells him to go to Girkin. Dubinskiy says he will be there in 20 minutes.

By now it has become clear to Girkin and Dubinskiy that they have downed a passenger aircraft, a Boeing.

3.6.5 Intercepted conversations about the downing of MH17 by a Sushka and the Sushka by a Buk

At this point the defendants went into action and the gist of their conversations changed. Their new account is that MH17, the passenger aircraft, was shot down by a Ukrainian Suhka and that they then shot down that Sushka with the Buk.

This is mentioned in a conversation between Kharchenko and Pulatov at 18:44.

Pulatov says that he is driving at full speed through Torez and that he has to provide a detailed evaluation of the situation. Pulatov says that Kharchenko has to tell ‘that one’ that ‘our Buk (...)’. Kharchenko interrupts Pulatov and tells him that everything is in order and that ‘that’ (i.e. their Buk) has gone to another location. Pulatov says that the Sushka downed the Chinese passenger aircraft one minute earlier. Kharchenko carries on talking and says ‘No, no, no. We were working over the Sushka.’ Pulatov says that he knows that and that shortly afterwards they had got the Sushka that downed the Chinese aircraft. Pulatov says that the whole world will be talking about it.

Fifteen minutes later, at 19:01, Pulatov received a call from the DPR fighter Tskhe. Pulatov says that he knows that he (Tskhe) is concerned but that the aircraft that Tskhe’s blood brother shot down was a Sushka, which had shot down the civilian aircraft one minute earlier. According to Pulatov, Tskhe’s blood brother has done well and Tskhe does not need to worry. This new scenario is also reflected in other conversations between separatists.

At 19:52 Pulatov gives the same account to Dubinskiy, although it takes a while for Dubinskiy to grasp the story.

Dubinskiy asks Pulatov: ‘Was our Buk fired or not?’ Pulatov answers that ‘the Buk shot down a Sushka after the Sushka had shot down the Boeing.’ Dubinskiy asks whether Pulatov saw this himself. Pulatov says that he himself was in Marinovka, but that their (‘our’) men had seen it from all positions and that it was observed from Snizhne itself. Dubinskiy apparently still cannot quite grasp it, and asks again whether the Sushka was shot down by ‘the Buk’. When Pulatov confirms this, the situation is clear to Dubinskiy.

It is not only Dubinskiy who initially has difficulty understanding the story. This becomes apparent two minutes later, when Dubinskiy calls Girkin to tell him the news.

Dubinskiy tells Girkin’s assistant that he needs to speak to Girkin and that it is very urgent. When Girkin gets to the phone, Dubinskiy asks whether he wants to hear some good news, probably the first today. Dubinskiy says that in Snizhne ‘our people’ saw the Sushka hit the Boeing, and that ‘our people’ had then hit the Sushka with the Buk. Pulatov has reported on these events. After Dubinskiy repeats that the Sushka hit the Boeing and that their people had then hit the Sushka with the Buk he asks whether Girkin thinks it is good news. Girkin replies saying that he doesn’t know but that he honestly doesn’t believe much of it.

As adamantly as Dubinskiy reports this ‘good news’ to Girkin, he himself seems unconvinced by this interpretation of the events. This is apparent five minutes later, a little before eight, when he is called by Kharchenko.

Kharchenko asks whether he should open up the crash site to the OSCE, the European organisation present at the crash site. Dubinskiy says he should. He then asks whether Kharchenko is sure that their people saw it being hit by a Sushka, or whether it was actually their people who were responsible. Kharchenko says they were not. Dubinskiy continues to ask questions: ‘It was Sushka, wasn’t it?’. Yes, it was a Sushka, Kharchenko says. ‘And then the Sushka was hit with a Buk by our people. Is that right?’ asks Dubinskiy. ‘Yes, first there was a bang in the sky and then our bang,’ Kharchenko confirms.

3.6.6 Conclusion

In the hours following the downing of MH17 there was a considerable amount of communication between DPR fighters, including the defendants. Initially they expressed their delight over the fact that a military aircraft had allegedly been downed. They referred to ‘our Buk’ and ‘the Buk’ that downed the aircraft. Once it became apparent that a passenger aircraft had been downed, the story changed to suggest that the Boeing had been downed by a Ukrainian combat aircraft and that this combat aircraft had then been downed by the separatists using a Buk. The defendants were still referring to ‘their’ Buk as having downed an aircraft.

It is not so surprising that not everyone accepted at face value the amended story – that in addition to MH17 a combat aircraft had also been downed – and that the conversations between the defendants were awkward; after all, no military aircraft was downed that day. There was not even a military aircraft in the vicinity that could have been targeted, or that could have shot down MH17. Extensive research has shown that neither the Russian nor the Ukrainian primary radar data from 17 July contain any record of a military aircraft in the vicinity of MH17. Witness statements and flight data provided to the Ukrainian authorities confirm that no military flights were carried out above separatist-held territory that day. Furthermore, no wreckage other than that of MH17 has ever been found.

As regards the evidence against the defendants, it is not important whether they sincerely believed that they had downed a Sushka or whether this was said merely to avoid being accused of downing MH17. What is important is that immediately after the downing of MH17 the DPR fighters, including the defendants, discussed the fact that they had downed an aircraft with their Buk. And given that no aircraft other than MH17 was downed in Ukraine on 17 July 2014, their conversations could only have pertained to the downing of MH17.

3.7 Removal of the Buk TELAR

3.7.1 Introduction

We have now considered at length the transportation of the Buk TELAR to the launch location on 17 July 2014, the launch of the Buk missile from the agricultural field near Pervomaiskyi and the reactions of the defendants immediately after the downing of MH17. We will now discuss what happened after the downing of MH17, i.e. the removal of the Buk TELAR to the Russian Federation and the role of the four defendants in this operation.

3.7.2 Organisation of transportation and security of the Buk TELAR

A few hours after MH17 was shot down various telephone conversations took place between the defendants and their subordinates about the removal of the Buk TELAR.

As we just mentioned, fairly soon after the downing Dubinskiy asked Kharchenko whether he was sure the Buk was in a secure location and whether it could possibly come under artillery fire. At this point Dubinskiy does not appear to have realised that MH17 was downed by the Buk, and so the conversation is confined to whether the Buk TELAR is secure. Kharchenko assures Dubinskiy that the Buk is safe. Over three hours later (at 20:30) – once the downing of MH17 has become world news – Girkin ordered Dubinskiy to have the ‘damaged tank’ ’evacuated’, under the escort of two BTRs (armoured vehicles). A group will be waiting for them at the regional border, he says, with a crane and a low-loader. Dubinskiy says that ‘the box’ is being guarded by Kharchenko and that he also has BTRs. Girkin refers to ‘the plane’ and says that Dubinskiy needs to sort it out.

Almost immediately after the conversation with Girkin, (at 20:32:44) Dubinskiy calls Kharchenko to say that a low-loader will come for ‘the box that we have’. He passes on Girkin’s orders: their two BTRs need to escort that box to the regional border. In reply Kharchenko says that he no longer has any BTRs: one has broken down and the other has been taken by ‘Prapor’, the call sign of another commander.

In these conversations Girkin and Dubinskiy discuss a ‘damaged tank’ and ‘the box’. Given the earlier and later conversations between the defendants that show that Kharchenko’s unit was guarding the Buk TELAR at that time, and given the facts and circumstances on the evening and night of 17 to 18 July 2014, it is unmistakably clear that ‘the damaged tank’ and ‘the box’ refer to the Buk TELAR.

3.7.3 Buk TELAR drives under its own power from launch location to Snizhne

As is apparent from the previously mentioned conversation between Dubinskiy and Kharchenko, the Buk TELAR was secured immediately after the downing of MH17.

3.7.3.1 Buk TELAR drives to Snizhne under its own power and under escort

It emerged from other conversations that the Buk was subsequently escorted to Snizhne. For example, in a conversation at 20:41 Sharpov tells Kharchenko that ‘the box’ is being removed by people unknown to him and asks Kharchenko whether he needs to escort it. Kharchenko replies in no uncertain terms that Sharpov should leave it where it is (‘don’t escort anything!’) and that he, Kharchenko, will come and pick it up. In the background Sharpov can then be heard telling others that Kharchenko is on his way to escort it. It is also said that they should go to the edge of the checkpoint, where Kharchenko will be arriving.

Historical telecom traffic data shows that from 16:26 to 20:54 Sharpov’s phone is transmitting to a mast that has the launch location and the nearby checkpoint in its range. Less than 15 minutes later, Sharpov tells Kharchenko that ‘it’ is now driving towards the town under escort and anti-aircraft artillery protection. Sharpov has heard that it will be guarded by ‘his own men’ and asks whether he should follow on behind them. Kharchenko tells him to let them go.

The fact that the Buk TELAR has left for Snizhne under its own power and is being escorted and guarded is also clear from the conversation that followed between Kharchenko and Dubinskiy. At 21:13 Kharchenko tells Dubinskiy that ‘the box’ has already gone. Dubinskiy wants to know whether the box left under its own power and where it is currently located. Kharchenko says that it did indeed travel under its own power and that it is now in Snizhne, adding that it will not go to its destination under its own power. Kharchenko is ordered to leave it there (in Snizhne); Dubinskiy is going to ask Girkin what they should do now. We will now play that conversation.

3.7.3.2 Buk-TELAR crew member lost before arriving in Snizhne

A number of subsequent conversations show that one of the Buk TELAR crew members became separated from the rest of his crew. In the conversation of 21:32 Gilazov informs Kharchenko that one fighter from the ‘launcher’ ‘has fucking lost his crew’. When Kharchenko asks which ‘launcher’ he is referring to, Gilazov answers ‘the Buk’. Gilazov says that the ‘fighter’ is still with him, at the checkpoint. Cursing, Kharchenko instructs Gilazov to take the fighter to Snizhne, where Kharchenko will be waiting for him.

Almost immediately after this conversation with Gilazov, Kharchenko called Pulatov and asked him to contact the fighters from the ‘new box’. Given the previous conversation with Gilazov it is obvious that he is referring here to the Buk TELAR. Kharchenko says that they are not at the meeting point and that they have also left one crew member behind. Kharchenko says that the crew member is with him. Pulatov promises to contact the fighters. Kharchenko then says that Gilazov (‘Ryazan’) is waiting for Pulatov at the Furshet supermarket.

Immediately after this conversation, at 21:42 on 17 July 2014 Pulatov called the phone number ending on 6335 three times. Pulatov tried to contact this number before, shortly after he met the Buk convoy with Kharchenko at the Furshet. As previously discussed, the user of this number is either one of the crew members or is in contact with the crew of the Buk TELAR. In the night following the downing of MH17 Pulatov calls this number three times but there was no answer. Given the conversation with Kharchenko earlier and his request to contact the fighters form the ‘new box’, the Public Prosecution Service assumes that at that time Pulatov was trying to contact the crew of the Buk TELAR or a member of the escort team. At 21.42 and 22.52 Pulatov was called twice by Gilazov, possibly about meeting the lost crew member at the Furshet. Immediately after these calls, at 21:53 and 22:53 respectively, Pulatov tried calling the phone number ending in ‘6335’ again, again without success.

Where and when the lost crew member rejoined the rest of the crew cannot be determined from the investigation findings. However, it is clear that while Kharchenko was responsible for the removal of the Buk TELAR, Pulatov was the one who maintained contact with the crew or the escort team.

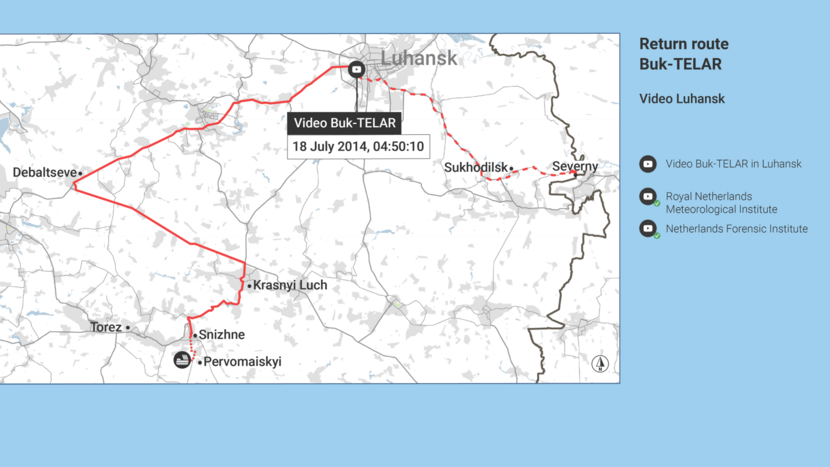

3.7.4 Transportation of the Buk TELAR from Snizhne to Luhansk

We have just discussed the departure of the Buk TELAR from the launch location and its arrival in Snizhne shortly after 21:00. The first instruction about the removal of the Buk TELAR came from Girkin and was passed on to Kharchenko by Dubinskiy.

3.7.4.1 Buk-TELAR convoy drives from Snizhne to Krasnyi Luch

Several hours later, at 23:12, Kharchenko told Dubinskiy that he was still in Snizhne and that the TELAR had just been driven onto the platform (of the low-loader).

Kharchenko says that he will have to escort the convoy to Debaltseve because nobody knows the way. When asked, Dubinskiy says that Kharchenko should leave the escorting to his (Kharchenko’s) boys. Two minutes later Dubinskiy calls Kharchenko and instructs him to drive to a crossroads north of Krasnyi Luch. He must wait there for the escort coming from Luhansk.

In this connection we would observe that the Buk TELAR would have to drive through the neighbouring Luhansk oblast in order to reach the open border crossing with the Russian Federation.

The Buk TELAR was ultimately escorted by Kharchenko’s subordinates, in line with Dubinskiy’s instructions to Kharchenko. One of them was witness S21, who drove one of the vehicles escorting the Buk TELAR and acted as point of contact for members of the LPR.

On the afternoon of the day MH17 was downed, witness S21 was at the Furshet supermarket. At the exit he spoke to two Russian-speaking men in uniform. In his statement he said that that evening Kharchenko had ordered him to escort the Buk TELAR from Snizhne to Krasnyi Luch together with some more of Kharchenko’s subordinates.

At a maintenance site for repairing equipment, located behind the Furshet, there was a low-loader carrying an air-defence system ready for departure. Witness S21 noticed the missiles’ fins and realised that it was a missile system, but only heard later from one of the escort team that it was a Buk TELAR. The two Russian-speaking men whom the witness had seen earlier that day at the Furshet were also present and got into the cabin of the low-loader. The convoy consisted of a Volkswagen Amarok, a black Volkswagen T5 and a low-loader with the Buk TELAR. According to S21 the convoy departed Snizhne for Krasnyi Luch at around 23:30.

This is consistent with the conversation that took place at 23:32 in which Kharchenko confirmed to Dubinskiy that his men had already left. Dubinskiy asks for the phone number of a senior member of the team, because this person will be called by ‘the ones from Luhansk.’ Kharchenko passes on the phone number and call sign of S21.

3.7.4.2 Planned escort of the Buk-TELAR by LPR fighters

Around the time that the Buk convoy is about to leave, the LPR fighters mentioned by Dubinskiy are preparing to meet the convoy at Krasnyi Luch and escort it onward to the border with the Russian Federation.

This is evident from the various conversations between the then self-proclaimed defence minister of the LPR, Plotnitskiy, and his deputy Bugrov. For example, in conversations at 23:34 and 23:46 Plotnitskiy tells Bugrov that a ‘Carpathian tree’ and two armoured vehicles needed escorting from the crossroads at Krasnyi Luch to the border crossing at Severny. This is where the convoy will be met. ‘Buk’ is the Russian word for beech, a common tree in the Carpathian region, hence the term ‘Carpathian tree’.

3.7.4.3 Buk TELAR convoy travels from Krasnyi Luch to Luhansk via Debaltseve

The planned meeting between the members of the DPR and the LPR and the handing over of the Buk TELAR does not ultimately take place. On the night of 17 to 18 July 2014 between 01:20 and 02:30 there are various phone calls that show that witness S21 and the rest of his group do not wait for the escort in Krasnyi Luch but instead continue immediately on to Debaltseve.

Two minutes later Dubinskiy calls back to say that he cannot get hold of Kharchenko and that he no longer knows S21’s phone number; he left it on Girkin’s table. Girkin decides to call himself. At 01:56 he says to S21: ‘The code word is 333. A guy will come along.’ Less than a minute later he adds: ‘Hello. Once again: they are to bring a barrel of diesel and after filling up they are to be escorted some distance off. Well, if they don’t bring a barrel that means they are the wrong guys. Got it?’ Within the next few minutes Girkin tries to contact S21 three more times. S21 finally answers on the fourth attempt. Girkin asks whether the handover was successful. S21 says that they are leaving for Snizhne. When Girkin asks whether he means that ‘the equipment’ has been handed over S21 replies: ‘I mean we went away in the direction of Snizhne. That’s it. Good bye.’ He then ends the call without answering Girkin’s question. Girkin therefore calls Dubinskiy immediately again. He asks whether ‘the equipment’ has now been handed over and says that it is ‘a hell of a mess’. He then gives Dubinskiy S21’s number. Dubinskiy says he has noted it and that he will call Girkin back shortly. It appears that he failed to do so, because five minutes later Girkin calls Dubinskiy again. Dubinskiy answers and says that he has not yet been able to contact S21. Girkin becomes angry and says that they have left and are heading back to the town. Dubinskiy asks why they would do that: after all, he had given them the instructions in Girkin’s presence. Girkin does not know either. What he does know is that it is a ‘hell of a mess’ and he tells Dubinskiy to sort it out. The ‘equipment’ must be handed over.

Six minutes later Dubinskiy still hasn’t been able to get in touch with Kharchenko or S21. Girkin reacts angrily. He says that the people from Luhansk came, but that one of the Dubinskiy’s men independently decided to turn back and now cannot be reached. He orders Dubinskiy to go to Snizhne. We will now play that conversation, from which it is clear that tempers are running high.

According to S21’s statement, the convoy arrived at the crossroads on the Rostov Highway near Krasnyi Luch at around 01.00 or 02.00 on the night of 17 to 18 July 2014. Around that time those escorting the Buk received several phone calls about other parties escorting the freight further but, according to the witness, no one in the group was aware of these arrangements so after a while they continued on to Debaltseve. Once they had arrived in Debaltseve, part of the convoy turned back to Snizhne. The rest continued on towards Luhansk with the low-loader carrying the Buk TELAR.

3.7.4.4 Buk TELAR convoy in Luhansk

The arrival of the convoy in Luhansk early in the morning of 18 July did not go unnoticed. The low-loader and Buk TELAR were captured there on video. This video was posted online that same day.

3.7.4.4.1 Luhansk video

The footage shows the Buk TELAR carrying three missiles, instead of four. In other words, one missile is missing. According to the metadata, this video was recorded on 18 July 2014 at 04:50:10.

This is close to the time determined by the KNMI on the basis of the images’ visual characteristics. The NFI investigated claims by the Russian ministry of Defence that this video had been manipulated. The NFI found no indication whatsoever of manipulation. On the basis of key features in the video and other image files on the memory card it was established that the video was filmed at a crossroads in Luhansk.

3.7.5 Transport of Buk TELAR from Luhansk to Russian border

From Luhansk the convoy is believed to have headed in a south-easterly direction via Sukhodilsk to Severny, the northern border crossing with the Russian Federation. This is a distance of approximately 63 kilometres.

3.7.5.1 S05’s witness statement

Witness S05 saw the Buk TELAR along this route early in the morning of 18 July 2014.

He stated that he saw the Buk missile system at around 05.20 near Molodogvardeysk. It was being transported on a trailer on the highway from Luhansk to Krasnodon. According to the witness the Buk was dark green in colour. The missiles were green with a white nose cone and were pointing in the direction the truck was travelling. He recognised the missile system as a Buk because on TV and the internet he had seen images of a Buk in Snizhne.

3.7.5.2 Chernykh calls Kharchenko

One of the men involved in the last part of the removal is Chernykh, als known as Bibliothekar. He was also involved in the transportation of the Buk to the launch location, on the route from the Russian border to Donetsk. Around the time that S05 saw the Buk on the trailer close to Molodogvardeysk, Chernykh’s phone pinged a mast (at 05.24) in the same town. No mast locations are available for this phone number between 05:24 and 07.15.

At 07:15 Chernykh’s phone pinged a mast in Severny, at the Ukrainian-Russian border. At that point Chernykh had phone contact with Kharchenko. The content of this conversation is unknown because neither of the numbers was being tapped.

3.7.6 Buk TELAR back in the Russian Federation

At 07:17, a few minutes after the contact with Chernykh, Kharchenko called Gilazov using the number that was being tapped. Kharchenko can be heard telling someone in the same room that everything is in order and that ‘the vehicle’ has reached Russia.

In the conversations that follow between the defendants they discuss the failed rendezvous and the fact that those escorting the vehicle couldn’t be reached. In a conversation at 07:41 Dubinskiy reacts to the events of the previous day. He is clearly irritated. He asks Kharchenko why S21 turned back. Kharchenko says that they escorted the vehicle to the crossroads and that the boys continued on their own. Kharchenko then says that the vehicle has arrived in Russia. A few minutes after the conversation with Kharchenko, Dubinskiy receives a call from Girkin. Dubinskiy says that the vehicle has been in Russia for some time and that everything went well.

Girkin asks Dubinskiy who S21 handed the vehicle over to. A few minutes later Girkin calls Dubinskiy again and tells him to send S21 to him. Immediately after the conversation with Girkin, Dubinskiy calls Kharchenko again. He says that Kharchenko needs to fetch S21 and bring him to him to explain who took the vehicle and where it was taken. According to Kharchenko it went to Bibliothekar, aka Chernykh, part of the group that had loaded the vehicle onto the trailer. They are now in Russia and are bringing along a new vehicle. We will now play that conversation.

Dubinskiy then calls Chernykh himself and asks whether ‘our men’ handed over the ‘box’ to him. Chernykh confirms this and says that he exported it and that it ‘is already there’, meaning the Russian Federation. Dubinskiy then informs Girkin that Chernykh received the vehicle from S21 and took it to the border area.

3.7.7 Conclusion

The Buk TELAR that was brought into eastern Ukraine in the night of 16 to 17 July 2014 was back in the Russian Federation a day later. After downing MH17, the weapon was loaded back onto the low-loader and driven to the Russian Federation under the escort of Kharchenko’s subordinates and under the direct responsibility of Dubinskiy, who was acting on Girkin’s orders.

3.8 Origin of the Buk TELAR

The intercepted calls and mobile phone mast data we have just discussed show that the Buk TELAR that was brought in on the morning of 17 July 2014 and removed again after the launch, came from the Russian Federation. Furthermore, this Buk TELAR has been identified as a TELAR belonging to the 53rd Anti-Aircraft Missile Brigade (which we will refer to as the 53rd Brigade) from Kursk in the Russian Federation. This identification took place in several steps.

3.8.1 Comparison of visual material from 17 and 18 July 2014

3.8.1.1 Ukrainian visual material

The first step in the identification process was the examination of the visual material of the Buk TELAR from 17 and 18 July 2014, which we will refer to hereafter as the Ukrainian visual material. The same Volvo truck and low-loader with the Buk-TELAR can been seen in visual material from Donetsk (I), Makeevka, Torez and Luhansk. A Volvo truck with a white cabin and a red low-loader is visible in all of this visual material.

In each case a blue stripe can be seen on the side of the cabin, with a (yellow and black) image above the blue stripe. In all of the visual material there are two orange flashing lights on the roof of the cabin, and on each side of the red low-loader there is a yellow sign with a telephone number printed in black. This white Volvo truck with low-loader appears to have come from the firm Budmekhanizatsiia in Donetsk. The firm’s owner recognised his truck in the visual material mentioned.

Furthermore, in the visual material from Donetsk, Makeevka and Torez, as well as that from Zuhres, a dark-coloured delivery van can be seen along with one or more escort vehicles. One of the other escort vehicles was a dark- or green-coloured jeep, also referred to as a UAZ in the case file. This can be seen in the visual material from Donetsk, Makeevka and Torez, as well as in the photo taken in Snizhne and posted on the Russian social media forum VK on the evening of 17 July 2014.

The Public Prosecution Service therefore concludes that the same military convoy – and thus also the same Buk TELAR – can be seen in all the visual material from 17 and 18 July 2014. The visual material from Donetsk (I and II), Makeevka, Torez and Luhansk is of such a high quality that a total of 15 specific features of the TELAR are recognizable. These are primarily traces of usage: features that point to wear and tear, transport or logistical markings for operational deployment. These include multiple transport markings and white stripes (or marks) in a place where tactical vehicle numbers are generally found. There was also a tear or opening in the rubber side skirt. And there is one anomalous road wheel on the right side of the TELAR.

This last feature is particularly identifying. In this investigation we only encountered two types of road wheels: with and without spokes. Generally a Buk-TELAR has one type of road wheels on each side: with spokes of without spokes. So, one divergent road wheel is special. Because the road wheels on the visual material from Ukraine is not always clearly visible, I now will explain how this deviation can be recognized.

If the sun hits a TELAR at a certain angle, a shadow can be seen in the wheel wells. Both the hub cap and the spokes in those wheel wells have an influence on the shadow. As a result, the road wheels with spokes cast a different shadow than the wheels without spokes. The shadow of the closed wheel is wider than that of the spoked wheels. On the basis of the differences in the shape of the shadow, it is possible to distinguish between the different types of road wheels.

The visual material from Torez shows the right side of the TELAR. In this image we see that all the road wheels have spokes, except for one: the second wheel from the rear, the second wheel from the left as we look at it.

Because the position of the sun and the shadows makes it difficult to distinguish the individual road wheels, the width of the shadow visible in each wheel was measured on the basis of the true dimensions of the road wheels.

On the basis of those measurements it is clear that the shadow cast by the second-to-last road wheel is substantially wider than that of the others. The width of the shadows in the other road wheels varies from 12cm to 15cm, while the shadow in the second-to-last road wheel is 23cm wide.

The calculations show an objective difference between the second-to-last road wheel and the other road wheels. Due to the distinguishing character of this feature, the shadows in the various road wheels were examined in more detail.

For this purpose 3D scans were made of Buk road wheels with and without spokes. These scans were then fed into a computer program that can run shadow simulations. By inputting the date, time and location of the TELAR’s position, it is possible to generate a simulation of the type of shadow cast by each type of wheel, using the actual weather conditions and position of the sun on the day in question. We will now show the results of that simulation.

If we now look once again at the visual material from Torez and compare it to the simulation of the shadow based on the actual position of the sun on 17 July 2014 at the recording location, it can clearly be seen that the shadow of the second-to-last road wheel – the right wheel as we look at it – is wider than the shadow in the other wheels, and is therefore a different type of road wheel.

We have now shown a number of features. A detailed description of all features can be found in an overview that will be appended to this closing speech. On the basis of the combination and location of all of these features, this Buk TELAR can be identified with a high degree of certainty. To establish the origin of the TELAR, the investigation team went in search of other visual material of a TELAR with exactly the same combination of features.

One of those other features is a white transport marking on the rubber side skirt. In the Russian Federation these kinds of markings are applied to military vehicles being transported by train. Due in part to this indication, investigators looked for visual material of Russian military materiel when searching for the same Buk TELAR.

3.8.1.2 Searching for the same TELAR in other visual material

On the internet visual material was found of a large military convoy that from 23 to 25 June 2014 was travelling south from Koersk in the Russian Federation along the Russian-Ukrainian border. The convoy, which comprised a complete Buk system including six TELARs, was last captured on film in Millerovo in the Russian Federation. The visual material consists of 21 video files and nine social media posts containing one or more images. We will hereafter refer to this as the Russian visual material.

The convoy included a Buk TELAR with a tactical vehicle number beginning with 3, followed by a small white stripe and ending in 2. This vehicle is also referred to as ‘3X2’. The most striking feature is that this TELAR also has one road wheel without spokes. This is clearly visible in the visual material from Stary Oskol.

The similarity with this distinctive feature necessitated further examination of ‘3X2’. This closer examination led to the conclusion that this TELAR has 14 of the 15 features visible in the visual material from Ukraine. The 15th feature in the Ukrainian visual material – a diagonal stripe left over from a tactical vehicle number on the left side of the TELAR – is not present on the ‘3X2’. Instead there is an almost complete vehicle number: a 3, followed by a small white mark and then a 2. This small white mark can also be seen in the Ukrainian visual material, next to the diagonal stripe. If we take a closer look at the shape of this diagonal stripe we see that this corresponds exactly with the shape of the 2 in the tactical vehicle number of ‘3X2’. This can be seen here.

If a vehicle is to be deployed in an operation, it is common practice to sand away or paint over the tactical vehicle number so that it cannot be identified. Because the contours of a 2 are still clearly visible (particularly in the visual material from Makeevka), the Public Prosecution Service concludes that what can be seen in the Ukrainian visual material – the white mark and the diagonal stripe – are the remnants of tactical vehicle number ‘3X2’. This explains the only discernible difference between the two TELARs.

When comparing features, it is important to look not only at whether they match but also at whether they are in the same position on the TELAR and the same position in relation to each other. And that appears to be the case not only with the remnants of the tactical vehicle number shown here, but also with all of the other features. We will show a few more examples here. Each slide shows a still from the Ukrainian visual material and a still from the Russian visual material.

On the first slide we can see a centre-of-gravity marking and a train transport marking adjacent to each other on the left side of the TELAR.

On the next slide we see a train transport marking on the right side of the TELAR which – unlike the marking we just saw – is located on the rubber side skirt.

Also on the right side we see just two white marks in the place where the tactical vehicle number is typically found. Unlike the remnants on the left side that we saw previously, these are positioned not next to each other but one on top of the other.

The aforementioned anomalous road wheel is also in exactly the same place on the vehicle in both the Ukrainian and the Russian visual material.

And finally, here is the tear or opening in the rubber side skirt that we mentioned earlier. Here too the tear is clearly on the same side of the TELAR and in the same place: between the road wheel without spokes and the adjacent road wheel with spokes.

Investigators thus established a match between the Buk TELAR captured in the images shot on 17 and 18 July 2014 in Ukraine and the Buk TELAR ‘3X2’ from the Russian visual material. In the opinion of the Public Prosecution Service, the combination of 15 features makes this TELAR unique.

3.8.1.3 Verification of the identification

The uniqueness of this combination became clear during the search for TELARs other than the ‘3X2’ with the same features. That was the third step in the identification process. More than one million photos and videos were secured during the investigation. The NFI developed a tool that could be used to automatically search for TELARs. From the full dataset of approximately 1.3 million images the NFI tool picked out 463.584 images.

These results were manually checked for relevance. This means that all 463.584 images were examined by human eyes. Only those showing one or more TELARs or parts thereof were selected. A total of 2481 images were labelled ‘TELAR’. This means that in all of these images one or more Buk TELARs or parts thereof are visible. These were Buk TELARs from both the Russian Federation and Ukraine. These images were examined multiple times, specifically looking for each of the 15 features. If one or more features were detected, the image was examined further to determine where exactly those features were located on that specific TELAR. This proved to be a painstaking and fruitless task: no Buk TELARs with the same combination of features as the TELAR in the Ukrainian visual material from 17 and 18 July 2014 and the ‘3X2’ in the Russian visual material were found in these images.

3.8.1.4 Sub-conclusion

The Public Prosecution Service therefore concludes on the basis of the three steps described that the TELAR that was captured several times in images shot on 17 and 18 July 2014 is the same vehicle as Buk TELAR ‘3X2’, which was captured several times in images shot on 23, 24 and 25 June 2014 in the Russian Federation. So the question is, where does this Buk TELAR come from?

3.8.2 Origin of the Buk TELAR

The answer to this question can be found in public sources, among other places. Internet posts by various people point to the convoy as having come from the 53rd Brigade in Kursk.

Firstly we would refer to an online forum for the mothers of military personnel from the 53rd Brigade, on which multiple messages were posted in June and July 2014. One of the posts in the forum is dated 6 July 2014. The mother in this case mentioned that her son had travelled with the 2nd battalion to the Rostov region bordering Ukraine in late June. In other messages this mother wrote that her son was serving in the 2nd company of the 2nd battalion of the 53rd Brigade. Her son’s identity and account can be deduced from her own VK account. On the account of this son – who for privacy reasons we will refer to as ‘the first soldier’ – a photo was found of him in military uniform with his name embroidered on it and an emblem of the 53rd Brigade. This photo was posted on his VK account on 21 June 2014.

Via the contact list of the VK account of the first soldier the investigation team found a second soldier, whose account contained a photo posted on 25 June 2014 showing him together with the first soldier. Both are wearing a military uniform. The VK account also contained a photo showing a name tag and the emblem of the 53rd Brigade. This second soldier also has an OK account containing a photo that features him sitting on a military vehicle in military uniform. This photo was posted on 24 June 2014. Under the photo are the words ‘on the way to Rostov’. A similar vehicle can be seen in two different videos of a military convoy posted on OK and VK on 24 June 2014. These are believed to have been filmed in the Belgorod district in the Russian Federation.

On the VK account of a third soldier there was a repost of a message from the second soldier. Both the original message and the repost on VK were from 25 June 2014. The post features a photo of several military personnel in uniform, including the second and third soldiers. An emblem of the 53rd Brigade is visible on their sleeves. Under the photos is the following text:

‘I’m heading to Rostov. ... We’ve already driven 700km... Our journey has already caused a lot of commotion)), we had only just left Kursk province when videos started being posted on YouTube)) it’s all very strange. It’s chaos in Ukraine) We’re driving in the direction of the war)’.

In response to a video of a military convoy, which was posted on the social media platform OK on 23 June 2014 and is part of the aforementioned Russian visual material, someone wrote: ‘my husband is in one of these cars’. While searching under her name the investigation team discovered a VK account. On this account there are photos showing a woman and a man. The man is wearing a military uniform with the emblem of the 53rd Brigade.

Further investigation was conducted into the number plates of the escort vehicles and low-loaders in the convoy of 23 to 25 June 2014. In a video posted on social media on 24 June 2014 five number plates can be seen which, on the basis of various publications on the internet, can be traced to the 53rd Brigade. There was also an investigation into a mailbox belonging to a soldier who was head of the Russian armed forces’ 47th Military Automobile Inspectorate in 2014.

His mailbox was found to contain transport orders for escorting the 53rd Brigade convoy in June 2014. These orders mention 13 number plates of escort vehicles and low loaders which were also observed in the Russian images of the convoy. One of these orders describes a route that is consistent with the route followed by the convoy in the Russian visual material.

3.8.3 Conclusion

On the basis of the comparison of visual material and the subsequent identification, the Public Prosecution Service concludes that the Buk TELAR that was captured on film several times in eastern Ukraine on 17 and 18 July 2014 is the same as the Buk TELAR bearing tactical vehicle number ‘3X2’ of the Russian armed forces’ 53rd Anti-Aircraft Missile Brigade, which from 23 June 2014 formed part of a convoy which travelled south from Kursk in the direction of the Ukrainian border.

The conclusion is therefore that flight MH17 was downed by a Russian Buk TELAR. This is consistent with the previously mentioned investigation findings showing that the Buk TELAR was transported from the Russian Federation to the launch location in the early morning of 17 July 2014 and following the launch was transported back to the Russian Federation.

3.9 The defendants’ statements and positions

3.9.1 Introduction