Response by the Public Prosecution Service. Delivered before the full-bench chamber of The Hague District Court.

Presentation of the public prosecutors on 12 November 2020

Introduction

Over the course of three days last week, Pulatov’s defence team submitted over 200 requests for further investigation. The court must also issue a decision on more than 80 such requests that were deferred in July. Today and tomorrow we will respond to these requests and advise the court about what decisions we believe should be taken.

In a few instances the defence rightly identified inaccuracies or omissions in the case file. For example, two staff members of the Ministry of Defence were identified as reporting officers in a summary official report and were also referred to as such in court when they were not, in fact, reporting officers.

In other instances the defence requested information that was already in the case file but not in the most logical place. That gives us the opportunity to indicate the correct place in the file. In those cases where the criticism expressed by the defence is valid, we will naturally rectify the omissions or errors they found and indicate where in the file the information in question can be found. In this way, this dialogue during the pre-trial review enhances the quality of the case file for the consideration of the merits of the case.

In addition to these pertinent observations, we have also heard a great deal over the past three days that we find perplexing. The case file is large and contains multiple documents of a technical nature. We also know that it is more difficult to grasp the contents of a case file if you were not personally involved in its assembly. So we can appreciate to a great extent the questions raised about the file and the critical approach taken. But our sympathy does have limits.

As it did previously in June, the defence has often requested information that is not only already in the case file but is also in the very documents cited in the request. Where relevant, we will discuss that later, occasionally illustrating our points with visual aids, so as to clear up any misunderstandings about this information.

As as it did in June, the defence has again misrepresented the content of certain documents. This begins with Pulatov’s video statement. The defence made the recording itself and the abbreviated version that was shown here in court. But in contrast to what the defence contends, at no point in the video do we do hear Pulatov mention an ‘anti-sniper device’ (memorandum of oral pleading, part 4 of 5, marginal number 163). We also do not hear him say that on the afternoon of 17 July 2014 he was around three kilometres from the launch site identified by the JIT (part 4 of 5, marginal number 477). Nor could this be inferred from anything else in his statement.

In the case file itself, we are often unable to find any textual support for what the defence concludes in its summaries. We would like to offer a number of examples. In light of the very large number of requests and the limited time available for this block of hearings, we will not run through all the factual inaccuracies in the defence’s argument. In any case, we regrettably had to conclude that we could not blindly rely on the reasoning presented in the requests; instead, we repeatedly had to return to the case file in order to check their assertions.

We were also struck by the defence’s practice of referring to the conflict situation in eastern Ukraine when convenient and ignoring it when that better fits their narrative. With regard to security risks to witnesses and the opportunities for conducting an on-site investigation, anything that departs from what might be seen in a shoplifting investigation in Badhoevedorp is characterised as noteworthy. The fact that MH17 came down in a war zone is apparently beside the point. Yet conversely, if the conflict situation can help the defence to explain away certain incriminating evidence or be used to justify requests for further investigation, we are evidently obliged to take it into account. Pulatov is of course free to adduce whatever arguments he likes, but it adds nothing to the debate.

We were also surprised to see that the Public Prosecution Service is accused of having an ‘rigid attitude’ in this case. We provided the court with an overview of all documents we shared with the defence for inspection and the visits to Gilze-Rijen we organised for the defence. In that overview you can see how little time passed between the submission of the requests and our granting of them. The court is also familiar with the correspondence between the defence and the Public Prosecution Service which shows that all reasonable, specific questions were answered swiftly. The defence has now requested and received dozens of documents, over a thousand digital photo files and more than a thousand telecom files, to study alongside the case file. In October we received an unsubstantiated, request from the defence to inspect the missile parts that had been found, a request we honoured at the shortest notice, even though it had been submitted far too late. Because we realise that the file is extensive and its contents complex, we have made a great effort from day one to offer the defence every support that could reasonably be asked of us, and more besides. Until shortly before the present hearing, the defence took full advantage of this.

It is indeed true that there were other defence requests that the Public Prosecution Service did not grant. This occurred if the requests were unreasonably broad or if their relevance was not evident. This was not due to a lack of will on our part, but rather a wish to respect the interests of other parties and prevent unnecessary work. The defence is now simply throwing requests at the wall in the hope that some of them will stick. Some of these arguments seem to vanish as soon as they are made. In June the defence expressly reserved the right to submit future requests for further investigation and present a defence related to combatant immunity. We assume that we will not be hearing anything more about this, now that we know that Pulatov acknowledged back in February that he was a volunteer in July 2014 and had left the Russian armed forces all the way back in 2008. On 10 June 2020 the defence indicated that it had information in its possession that the user ‘Khalif’ on the forum Glav was not Pulatov. Multiple requests on our part to provide us with that information so it could be examined went unanswered. Now that Pulatov has issued his own statement, which overlaps in certain key respects with previous comments by the user ‘Khalif’ on Glav, we assume that the defence will also drop this point. In June the defence asked the Public Prosecution Service to make available several thousand intercepted telephone conversations for the purpose of their own investigation into the relationship between Pulatov, his co-defendants and other individuals, and in order to have a better sense of Pulatov’s tasks and activities, among other things. Pulatov’s position and activities are described at length in the case file on the basis of various sources and are not disputed by Pulatov. This is why that request was only granted in part. Last week, Pulatov himself stated that Girkin and Dubinskiy were in charge and that he worked with Kharchenko. He also spoke about his tasks and activities in July 2014. All this is largely consistent with what is in the case file. The question remains whether Pulatov merely worked with Kharchenko or if he actually was in command of the latter, in view of the orders given in various intercepted conversations, but this does not matter for the assessment of the indictment. It is a mystery to us why the defence asked for intercepted conversations for the purpose of assessing information that Pulatov himself has now confirmed. We are also unclear about the purpose of all the requests submitted last week to examine deceased persons as witnesses.

The crux of this pre-trial review is the determination of what further investigation is needed in order to a) have all the information the court needs to properly assess the charges and (b) to ensure that this is a fair trial in which the defendants have every reasonable opportunity to present their positions with well-founded arguments.

The Public Prosecution Service is concerned above all with ensuring that requested investigations are conducted if they genuinely help to shed light on the truth. No one benefits from the conviction of an innocent person — not the defendant, not the police, not the Public Prosecution Service and not the next of kin. In this investigation and in this trial we are seeking to establish, to the best of our ability, what happened on 17 July 2014 and who is responsible, in order to ensure justice for the 298 victims. If further investigation can shed new light on the facts of the case, we are all for it. As we said back in March: we will go where the evidence takes us, and only there.

At the hearing back in June we noted that the defence likes to present itself as a seeker of truth but that is not the case. We see this again now: the defence asks for leeway to do everything it deems necessary as a self-styled seeker of truth. Once again it invokes the many years the investigation has taken and suggests that it too should be given abundant time (see, for example, part 2, marginal number 4). That suggestion ignores two key facts. Firstly, investigations have been conducted over the years not only by the JIT and the Public Prosecution Service but also by numerous other parties, including the Russian Federation and many critical journalists (both professionals and citizen journalists). And during that time, for example, the scenario that MH17 was shot down by a fighter aircraft has been dismissed not only by the JIT but also by the Russian Federation. The pathways that the defence is now seeking to revisit have already been explored by many others and incorporated into the investigation of the last few years by the JIT and the Public Prosecution Service. The results can be found in the case file.

Secondly, the defence is not Sherlock Holmes, nor a UN commission of inquiry; it is the voice of the defendant Pulatov. And a defendant does not function as an alternative investigative agency at his own trial. He is entitled to put forward his viewpoints, and he can call for further investigation if he can provide good reasons for doing so. He must, however, specify in a timely manner what the goal of the requested investigation is. A desire to verify everything is not sufficient. As we said back in June, echoing Amsterdam Court of Appeal: a defendant’s right to be granted the opportunity to dispute the methods and results of the investigation does not constitute an unconditional right to evaluate them. In a fair trial there are also limits to what defendants can request and how much time they are granted for that purpose. A defendant has the right to an effective defence, but not the right to determine the substance of the trial or how long it takes. If a defendant wishes further investigation to be conducted, he must submit a request in a timely manner and explain why the outcome of that investigation is relevant to the decisions the court will take in his trial. This is how we assess requests for investigation.

After this introduction, our response is structured as follows:

we will begin by discussing the standards by which requests must be assessed. We will then discuss the various requests that have been submitted. In doing so, we will more or less follow the order used by the defence:

- Question 1: was MH17 downed by a Buk missile?

- Question 2: was the Buk missile fired from an agricultural field near Pervomaiskyi?

- Question 3: was the defendant Pulatov involved?

Then we will turn our attention to the defendant’s questions about the case against the Russian Federation at the European Court of Human Rights.

After that, we will discuss the requests for investigation deferred in July and a number of requests for investigation formulated today by the Public Prosecution Service in response to issues raised during this block of hearings. We will then consider the question of how to efficiently carry out the requests for investigation that have been granted, and we will make a number of requests regarding the consideration of the merits before a brief conclusion.

Standards for assessing a request

Earlier in this hearing we already discussed the fact that Dutch law recognises two different standards for assessing requests for further investigation on the part of a defendant: the defence criterion (verdedigingsbelang) and the necessity criterion (noodzakelijkheidscriterium).

Back on 3 July 2020 the court announced it would make a decision about the criterion by which requests for further investigation would be assessed in this block of hearings after the defence explained why they had not been submitted earlier.

We will now discuss two issues in relation to the assessment framework: the point at which the requests were submitted and the matter of whether the existence of multiple anonymous witnesses in this case has any bearing on the standard.

Time of submission

It is the position of the defence that all requests that have now been submitted should also be assessed in a manner that is not essentially different from the ‘defence criterion’. In support of this, the defence refers to the nature and size of the case file, the need to coordinate with Pulatov and other defence activities. The Public Prosecution Service is unable to follow this line of reasoning. There have been no significant additions to the file for quite some time. It was in response to the defence team’s own request that they were afforded the opportunity to review a large number of irrelevant digital files; moreover, this material came with a warning from the Public Prosecution Service that the granting of their request did not imply that those thousands of files were relevant.

All the circumstances cited by the defence have been known for some time. The size of the case file and the need for sufficient time to review it were already known when the defence told the law journal Advocatenblad that it would be able to take on this job with all the staff at its law office. And all the other circumstances mentioned were already known when the defence announced in June that it intended to submit those requests for further investigation that required no additional consultation with Pulatov within eight weeks.

The fact that Pulatov eventually decided to make a statement at this trial is a positive development, but he must also bear the consequences arising from the lateness of that decision. As far back as June 2019 the JIT attempted to question him, and in December 2019 he was given the opportunity to tell his side of the story via the Russian authorities. He declined both opportunities. Pulatov has had legal assistance in this case since 16 October 2019, and since late 2019 the Public Prosecution Service has repeatedly asked him if he intended to make a statement, first through his Russian lawyer and later through his Dutch legal team. The fact that Pulatov ultimately chose to record a video statement in October 2020 cannot be an excuse for failing to submit requests for further investigation that can be formulated without further consultation by the end of the September block of hearings, as stipulated by this court in early July.

It is now even clearer that many of the newly formulated requests for further investigation could have been submitted much earlier, given that we now know what Pulatov told his legal team back in February 2020, before the trial had even opened. Even before the start of the trial in March, the defence was aware of Pulatov’s standpoint that he knew nothing about the transport or the presence of a Buk TELAR in eastern Ukraine or the cause of the downing of flight MH17, and indeed he believed it was impossible that a Buk TELAR could have been transported to the launch location identified by the JIT. One of the issues discussed at the hearings in March and June was whether it was necessary to examine multiple witnesses to that transport. At that time the defence had every reason and opportunity to submit the requests for witnesses that were not submitted until November this year. It was already clear before March that Pulatov disputed the possibility that witnesses could have observed what they claimed, but that he had no direct knowledge he could share about the subject. After March, the defence could have submitted these requests in June, August or September. The fact that they allowed all those opportunities to pass cannot be dismissed with a simple stroke of the pen. This is especially true if we take account of the fact that Pulatov has been commenting on this trial online from the very start. Anyone who could take to the internet as far back as April 2017 to explain that at the time of the downing of MH17 he was ‘in the vicinity of Stepanovka’, that the ‘missile launch trail from Snezhhoye was not visible’ and that spotters had reported that ‘a high-flying aerial target had brought down another aerial target with an attack’ could also be considered capable of offering that explanation in the various blocks of hearings that took place in the first nine months of 2020 and to formulate requests for further investigation prompted by such an explanation.

The same applies to the requests to examine experts from the NFI. Back in June the defence made extensive objections, with the help of a flow chart, about the possibility that experts could have been influenced by ‘contamination’ and submitted requests for an investigation into the findings of the forensic investigation. The fact that they are only now, in November – three blocks of hearings later – formulating the requests for investigation relating to the position they took in June cannot be understood without further explanation. The statement that Pulatov has now submitted is irrelevant to those categories of request.

Anonymous witnesses

The use of an anonymous witnesses in a criminal trial creates difficulties for the defence because it means they have less information than usual and cannot fully exercise their right to confront such witnesses. In that light we can fully understand the defence’s complaints about the amount of redacted information in the case file. We would also have preferred that the situation were otherwise. But the security risks facing witnesses in this trial are a fact which ‘unfortunately’ must be taken very seriously.

The question may arise whether we should be more accommodating when it comes to Pulatov’s requests to examine witnesses about whom information in the case file has been redacted. This would seem to be the position of the defence, given the scant grounds it offers in support of allowing the examination of numerous protected (226a and 149b) witnesses. Their reasoning in this regard would seem to be that, even without offering specific grounds in support of their position, the defence must be given a great deal of leeway to assess the reliability of witnesses because they do not have the full interviews at their disposal.

The law takes a different position on the matter. Various compensatory safeguards are built into the Dutch legal system so that the use of anonymous witnesses does not infringe on the right to a fair trial as laid down in article 6 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). For example, the independent examining magistrate who examines the anonymous witness is obligated to investigate the reliability of that witness and to draw up an official report on that subject, which will be added to the case file (article 226e, Code of Criminal Procedure). The law also stipulates that if the defence is not allowed to be present for the questioning of the witness because this would not be in the interest of shielding their identity, the prosecution is also not allowed to be present (article 226d paragraph 1, Code of Criminal Procedure).

The court, which will ultimately decide if the statement given by an anonymous (threatened) witness is reliable and thus can be used as evidence, is also bound to stricter rules than apply to witnesses whose identity is not shielded. For example, such a statement can only be used in connection with serious criminal offences (article 344a paragraph 2, Code of Criminal Procedure) and a finding that a given charge has been proven cannot rest solely on a statement by an anonymous witness (article 344a paragraph 1, Code of Criminal Procedure). Finally, the court must evince more grounds than usual to explain why it considers that a statement by anonymous witness is reliable. Taken together, these provisions serve to compensate the defendant for the fact that he is unable to fully exercise his right to examine witnesses.

Naturally, these rules also apply to the present proceedings. Time and again, the examining magistrate conducted an extensive and thorough investigation into the reliability of each witness and their statement. The results of that investigation are set down in an official report that has been added to the case file. This report explains such matters as how the examining magistrate verified the manner in which the witness was found by the investigation team, what contact the witness had had with others, and what prompted the witness to give a statement. It also explains how checks were performed to determine whether the statement made to the examining magistrate matched the previous statement given by the same witness to the police. The examining magistrate also assessed whether the statements were coherent, logical, plausible, consistent and detailed, and whether they were in line with the evidence in the case file and with information from public sources. In the spirit of honouring the principle of an ‘equality of arms’, neither the defence nor the prosecution were present for the examination of the anonymous witnesses.

These are all compensatory measures that were included in the law specifically because the defence cannot fully fulfil its role in assessing the reliability of threatened anonymous witnesses. So the complaint voiced by the defence that it faces restrictions with respect to assessing the statements of various witnesses is legitimate. But by law the compensatory mechanisms offsetting these restrictions rest with the examining magistrate and the trial judge. Thus, these restrictions do not call for a more accommodating attitude towards requests for additional investigation or for lower standards with regard to the grounds in support of such requests. Rather, the defence may be expected to be able to argue, with even greater precision than would be the case for a non-anonymous witness, what exactly they wish to ask the witness. After all, an examination on issues that were expressly excluded from the case file by the examining magistrate is plainly impossible. To grant such a request would undermine the decision-making power reserved to the examining magistrate. This would constitute an unacceptable interference in the statutory powers granted under our system of criminal procedure. The inability to examine a witness, anonymous or otherwise, does not in itself violate a defendant’s right to a fair trial. The decisive factor in this connection is whether the trial as a whole was fair.

Conclusion

There is thus no reason, generally speaking, to offer the defence the benefit of the doubt when it comes to the lateness of these requests for further investigation or to the grounds underlying the request to examine anonymous witnesses. An individual assessment must be made of every request for further investigation, or every category of related requests, in order to determine whether objectively sound reasons exist as to why the request was not submitted earlier. Since the defence has not adduced such sound reasons, we see no grounds for a more accommodating interpretation of the necessity criterion for requests for investigation in this block of hearings.

From the perspective of efficiency, we will only discuss the standard (the necessity criterion or the right to mount a proper defence) if it is relevant to the decision to be taken by the court. If we conclude that a given request should be denied without discussing the standards applied, that means that we reached the same conclusion under both options. After all, if a request for further investigation is not allowable – due to, for example, insufficient grounds or a lack of relevance – the court is not required to mention in its decision what standard applies to the investigation.

Response to forensic investigation (part 3 of 5)

Introduction

In part 3 of 5 of the memorandum of oral pleading, Pulatov makes several requests concerning the forensic investigation. Most of these relate to examining experts with regard to reports included in the prosecution case file.

The court already granted several such requests back in July, including the examination of multiple experts, which are now again the subject of requests. We will now discuss these various requests. Before doing so, we will begin with a short introduction to the statutory framework as regards requests for the examination of experts. By first setting out our guiding principles for the assessment in general terms, we will be able to be briefer when we subsequently come to discuss the various requests.

The purpose of questioning an expert is to obtain information. A request to examine an expert cannot, therefore, be an advance statement of the defendant’s case, but must specify what relevant information the expert in question has not yet provided. The defence must, moreover, submit the request to examine experts in time. If a request could reasonably have been made earlier, the late submission may be instrumental in a decision to reject the request. The court has already determined that in this phase an explanation is required of why requests were not made earlier, in order for the necessity criterion to be assessed from the proper perspective. We have already concluded that there are no reasons to justify, in a general sense, the late submission of all the investigation requests that have now been made. That is especially true of the requests to examine forensic experts, since we stressed the time-consuming nature of such examinations back in March, and Pulatov himself made similar requests – concerning the same matters and in some cases the same experts – back in June. Pulatov does not explain why he did not make these requests at that time, or why he subsequently did not make use of the hearings held on 31 August and 28 September either.

Furthermore, relevant questions put to an expert about a report must relate to the investigation that was performed and must be confined to the expert’s area of expertise. The information to be obtained under examination must be specifically identified. Generalities are not sufficient. It is thus not sufficient to indicate that the defence ‘has questions’ about a given subject or report: those questions must be formulated in a sufficiently specific manner, so that the court can assess whether they indeed remain unanswered (in the case file as a whole) and whether they are relevant. The defence’s position that it has questions about the methodology used in a given investigation, for example, is merely a general announcement of questions that otherwise remain unspecified, and therefore it is insufficiently specific to justify such a request. An examination of witnesses is not important or necessary if the only questions to be posed are of secondary importance and the answers to those questions cannot influence the outcome of the criminal proceedings.

The fact that a defendant does not agree with the substance of a certain expert report or wishes to dispute the expertise of the author is not an independent ground for conducting such an examination. An examination, after all, is not a statement of the case. The matter at issue is always what specific information which is not yet in the prosecution file and is relevant to the criminal proceedings can be produced by examining an expert.

In its explanation the defence first makes a few general observations that are intended to form part of the basis for the requests. We will run through them briefly.

General observations

The expertise of the reports’ authors (marginal no. 17)

In support of his requests Pulatov first argued that none of the NFI reports described the precise nature of the training and experience of the experts who reported their findings. The defence thus fails to take into account that the examining magistrate explained elsewhere in the file the grounds on which in each individual concerned was designated as an expert. In doing so, the examining magistrate devoted attention to the training and assessment of the experts by the NFI and the fact that these experts all operate within the NFI’s accredited quality system. This explanation is only logical, given that the NFI is one of the world’s leading forensic institutes. The NFI conducts investigations not only for the Dutch criminal justice system but also for various international criminal tribunals.

If Pulatov wishes to verse himself further in the expertise of the individuals who reported their findings, he will find plenty of information in public sources. There are, for example, the many scientific publications that several of these experts have published in their field, not to mention the published case law in which their other investigations are discussed. These are established NFI experts who are tasked with reporting findings for the purpose of legal proceedings and who have been designated as experts on numerous occasions by various courts, including prior to 2014. There is thus no shortage of information available about the expertise of these individuals.

‘Contamination’ (marginal nos. 17-26)

Next, Pulatov wonders whether the reliability and credibility of the reports and their substance should be called into question, since it is possible, in his view, that the information in them has been contaminated. The defence is referring not to contamination in the sense of the adulteration or mixing of evidential material, but to the possible influencing of the experts by the information they obtained. It points out in this regard that the experts reported on their findings several times in this investigation, and also read other reports regarding the case, such as that of the Dutch Safety Board. The fact that the experts performed successive analyses on several occasions is also described as potentially hampering their ability to perform subsequent studies with an open mind.

The influencing of experts by information they receive can be a relevant point of concern when it comes to assessing the results of expert investigation. However, the relevance varies widely depending on the type of investigation. When an expert expresses an opinion on the likelihood of different hypotheses, for example, contamination is a more relevant concern than in the case of metallurgic investigation, which by its very nature is aimed at establishing the elemental composition of the material concerned. For this reason, the defence’s approach is too general.

Pulatov also sees problems where they do not exist. Take the statement that the information received that the aircraft, according to Ukrainian government sources, had been hit by a Buk missile system, would rule out an explosion inside the aircraft as the cause of the crash (marginal no. 54). This ignores the fact that this information was not a point of departure or an obstacle for investigators. It merely makes clear that the investigators – like the rest of the world – were aware of the Ukrainian government’s contention that a Buk missile was the cause. This can easily be seen in the case file, since NFI investigators not only provide reasoned explanations of which findings point to an explosion outside the aircraft, but also explicitly indicate those findings about which the same cannot be said.

Secondly, it makes the problems raised by the defence rather academic, since up until now the defence seems also to have worked on the assumption that flight MH17 was attacked from outside, and not inside, the aircraft. In June, for example, the defence indicated that it was exploring lines of investigation which it believed should have been followed ‘after it was concluded that an explosion from inside should be ruled out.’ The defence does not appear to dispute the conclusion that an explosion from inside the aircraft can be ruled out. Nor did the Public Prosecution Service hear anything further about this matter last week.

All in all, Pulatov only poses open questions about theoretical possibilities concerning the influencing of experts, without producing a single concrete indication this actually occurred. As we will explain when discussing the individual requests, no such indications exist.

On the contrary, the file does contain concrete indications that the various experts performed their work freely and with an open mind, and that they amended or qualified their conclusions if subsequent investigation justified doing so. This was the case, for example, with the examination of differences in the elemental composition of the variously shaped fragments contained in the warhead of a Buk missile, and with the comparative study of metal fragments recovered from the left wing and the ‘sweepings’, the missile engine casing and reference material.

A further compelling question is why Pulatov is only now submitting these requests. No explanation is offered as to ‘why now’, even though defence had already discussed in detail (back in June) the alleged danger of experts being influenced by contextual information, including in relation to the NFI investigation that is now the subject of renewed debate. The defence therefore had every opportunity to make these requests back in June or September.

Given the vague nature of the defence’s observations, and the late submission of these requests, we do not see the necessity of further investigation on this point.

Scope of investigation (marginal nos. 27-36)

Pulatov makes various observations about the scope of the forensic investigation: i.e. what was and what was not subjected to forensic examination. This too is a matter on which Pulatov believes experts should be questioned. Here the defence ignores the fact that the scope of the forensic investigation is determined not by the experts but by the Public Prosecution Service and the examining magistrate. This ‘scope’ is formulated by them in the investigation instructions, which are carried out by the experts and forensic detectives.

Given that an appointed expert thus performs investigative activities at the behest of the examining magistrate, and that those activities are performed within the parameters of the investigation instructions, there is no reasonable interest in asking about investigative activities not performed by the expert. The predictable response, after all, will always be that the expert received no instruction from the examining magistrate regarding such an activity. The case file, incidentally, contains multiple reports by experts indicating that additional investigation was needed, and instructions were subsequently issued in respect of such investigation.

If the defence is of the opinion that certain investigative activities were neglected, it can request a more detailed explanation from the Public Prosecution Service or the examining magistrate. It can request the court to order those activities now, or it can refer to the lack of that investigation when stating its case.

Asking experts why certain investigative activities were not performed is pointless, moreover, if other documentation in the prosecution file shows that the activities in question were performed, but were covered in another part of the file. That is the case, for example, with the alleged ‘one-sided focus on the Buk missile’ (marginal nos. 27-29 and elsewhere). As we explained back in June, there was an extensive investigation into whether any other weapon could have been used to shoot down flight MH17. If the defence believes that there are grounds for forensic investigation in which recovered trace evidence from MH17 is compared with reference material from a particular type of weapon that is not a Buk missile, we are very willing to hear about it. The defence must, however, indicate the specific facts and circumstances on which it bases the conclusion that investigation into a specific weapon could be worthwhile. If the defence is unable to do that, we are forced to conclude that although they perhaps would like there to be another type of weapon in contention, they are unable to substantiate this.

Requests

Following that general overview, we come now to the individual requests. We will stick to the order and lay-out used by the defence.

NFI request forms (marginal no. 21)

Pulatov has requested that the examining magistrate ask for all the request forms held by the NFI and add them to the file. This is a request to make use of your power under article 315 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, meaning that the necessity criterion is the applicable yardstick. No explanation has been given for why the request was not made earlier. Request forms are internal administrative documents. Their use is part of the NFI’s standard working procedure. The information contained in the forms that is relevant to the criminal proceedings, such as the questions asked, an overview of material to be examined and the information provided to the NFI along with the request, is always copied from the forms and included in the reports. Therefore, the requested information can already be found in the NFI reports. There is no reason to think that this request to the examining magistrate will provide any relevant additional information.

Primo-03956 (marginal nos. 37-45)

The request to examine the authors of the 2015 report no. 03956 is based on two grounds:

- questions about the investigative methodology that was used;

- questions about the findings and conclusions.

However, the reasoning provided in this connection is inadequate. The question regarding the methodology used concerns the investigative methods LA-ICP-MS and PCA. In the world of forensic science, LA-ICP-MS is a standard investigative method which has for some time been used in laboratories around the world. It is described in an NFI document that is appended to the report in the file. PCA is commonly used method of statistical analysis. A great deal of information about it is available in public sources. If the defence has concrete questions or suspicions concerning the use of these investigative methods for this specific investigation, it can of course put them forward. However, merely announcing that the defence wishes to ask questions about ‘the methodology used’ is not sufficiently concrete.

Nor do the questions raised about the findings and conclusions provide grounds for examining the experts about this report. The first question raised concerns the visual similarity between the recovered bowtie fragments from MH17 and the shape of the bowtie fragments in the dismantled missiles that served as reference material. That visual similarity can be observed by anyone on the basis of the photos in the file. There is no need to examine an expert about this.

A further question concerns the basis for the conclusion that recovered metal fragments which, in their elemental composition, closely resemble recovered bowtie fragments were originally bowtie-shaped. The report is indeed technical in nature, but the conclusion is clearly explained: analysis of the reference material showed that the differently shaped fragments in a warhead also differ in their elemental composition. In an analysis of elemental composition, the filler, square and bowtie-shaped fragments thus comprise distinctive groups. The report therefore explains that it is likely that fragments which have the same elemental composition as fragments still recognisably bowtie-shaped were originally bowtie-shaped too.

It should be noted however that this is a report from 2015, and that this conclusion was qualified somewhat in the later report Primo-9472. This is relevant to the assessment of Pulatov’s investigation requests in three ways. First, it shows that the prosecution file offers sufficient information about the course of the forensic investigation over the years: since many reports, from various years, are included, the reader can properly follow the course of the investigation. Second, this is also an example of the open-minded manner in which the NFI’s experts performed their investigation. They revised or qualified their conclusions as their subsequent findings dictated. Finally, all this also puts into perspective the importance of examining experts about the 2015 report Primo-03956: other reports from subsequent years offer more, and more current, information about the subjects raised by Pulatov in this regard.

This last point applies equally to the final question raised by the defence, concerning the layers of aluminium found on metal fragments (marginal no. 45). Firstly, it is striking in this regard that the defence cited only part of the relevant passage from the report, as if this were the entire answer. The answer to the question referred to in this passage can be found elsewhere in the report. At the start of the report, it is explained that ‘reference material’ refers to ‘cockpit glass and aluminium from the aircraft fuselage’ (p. 6). The cockpit glass and aluminium are then discussed in the conclusion (p. 24). The defence can thus find the answers for itself in the report. In so far as this report leaves certain questions unanswered about (the origin of) the aluminium found on the metal fragments, those questions are answered in other, later reports in the case file.

In short, the grounds given for this request do not make clear that any genuinely new or relevant information can be obtained from the requested examination. Therefore, for want of interest or necessity, the request should be denied.

Primo-09427 (marginal nos. 46-53)

In addition, Pulatov wishes to examine the authors of the report Primo-9427. This report deals with the investigation into the elemental composition of recovered pieces of warhead fragments and reference material. No explanation has been given for why this request has only been made now. The request must therefore be assessed in accordance with the necessity criterion. We can find no need in what has been adduced that would justify conducting an examination. The defence cites a single paragraph from the report, observing that it raises questions. We do not see why. To us it seems clear that this passage means that the fragments found in MH17 could not, in any event, have come from the warheads used as reference material. After all, this reference material was still intact when it was made available to the investigation, and as such it could not have been involved in the downing of flight MH17. However, since there were similarities in their elemental composition, the fragments found in MH17 and the fragments from the reference material could have both come from the same production source.

The only other question posed by Pulatov relates to investigative activities that these experts did not perform, namely whether it was possible to rule out that the fragments had come from another weapon (marginal no. 53). In this report the authors rule absolutely nothing out, but rather report on likely relationships. What is more, this subject is clearly outside the authors’ area of expertise: they are experts in micro analysis of trace evidence and materials, and in forensic elemental analysis. In their report and conclusions, they do not claim to be weapons experts, and they should not be invited, in some future examination, to express an opinion on surface-to-air or air-to-air missiles that they have not themselves investigated. This request too should therefore be denied, since its grounds are insufficiently explained and it has only now been submitted.

Primo-04162 (marginal nos. 54-63)

The defence next makes a number of observations and poses several questions about Primo-04162. Before discussing those questions and observations, it is worth pausing to consider the investigation described in that report. The investigation concerned the many fragments that were recovered from one particular body, which were submitted to the NFI with a request to examine whether they bore any relationship to an explosion occurring inside or outside the aircraft. In this investigation no comparison was made to reference material or to fragments recovered from other bodies or pieces of wreckage. And this is only logical, since the investigation was assigned verbally as early as 23 July 2014, and confirmed in writing on 28 July 2014.

The defence incorrectly states that a sentence appearing in the chapter ‘Information obtained’ – to the effect that the Ukrainian authorities believe MH17 was hit by a Buk missile – would rule out an explosion inside the aircraft. At the time, the investigation had yet to begin, and the assignment was clear: investigate whether any relationship could be found to an explosion outside or inside the aircraft. The sentence concerned merely provided context to the assignment and its constituent questions. It was a context, moreover, that at that time was the subject of world news and of which the relevant experts could be presumed to have been aware.

Next, the defence wonders how much freedom the report’s author had to reach a different conclusion from that given in two other reports he had written, the aforementioned reports Primo-3956 and Primo-9427. As the Public Prosecution Service has explained previously, there is no basis in the file for the concern about influencing. This instance is no different from the other in that regard. The defence incorrectly states that the findings in the report Primo-4162 were not made until 2017 and not reported until August 2017. Yet the defence, in its own explanation for the examination request, emphasised that this was a revised report, and the report shows that the previous report had been drawn up in May 2015. It also shows, moreover, that the revision related only to a few incomplete details, and that the conclusion had not changed. Therefore there can in any event be no question of the later findings from Primo-9427 exerting any influence on the report’s author, since these findings were not yet known at the time of this investigation. The same can be concluded with regard to Primo-3956. Not only did this involve a different type of investigation, but the investigation material dealt with in Primo-4126 was made available by the NFI well before the complete investigation material dealt with in Primo-3956: 4 August 2014 versus 25 March 2015.

The defence then identifies three passages in the report as the ‘most striking question marks’. We will now discuss those passages.

The defence does not understand what findings are being referred to in the sentence: ‘[On the basis of] the above-mentioned findings, it is suspected that the steel fragments came from a weapon that exploded outside the aircraft.’ Yet the findings in question are described in detail starting on page 13. The description of those results shows, for example, that another material was found on the fragments. The elemental composition of this glass-like material (which comprised sodium, aluminium, silicon, oxygen and zirconium) was consistent both with that of cockpit glass from a Cessna, which was available as a reference material at the NFI, and with the cockpit glass recovered from the wreckage at the air base in Gilze-Rijen. Other pieces of non-cockpit-window glass recovered from the wreckage and examined did not contain zirconium. Nor do other common forms of glass, such as window panes, car windscreens and phone screens contain any zirconium. In addition, the NFI expert noted that the steel fragments contained several explosive ‘signatures’, consisting mainly of morphological characteristics such as warped surfaces.

It is these findings that, in the text leading up to the sentence in question, form the basis on which ‘it is suspected that the steel fragments came from a weapon that exploded outside the aircraft’. This is not unclear. We are talking about pieces of steel recovered from the body of one of MH17’s occupants, which appear to have been warped by an explosion and on which melted cockpit glass was found. A careful reader of the report will understand that these steel fragments probably came from a weapon that exploded outside the aircraft. No additional explanation by an expert is necessary.

The defence further claims not to understand what is meant by the sentence, ‘The similarities between these fragments and reference material from possible weapon systems will be investigated further.’ Here, the defence wrongly states that this sentence was first written by the NFI in 2017. The careful reader will see that both the period of time involved and the further investigation referred to by the NFI are different to what the defence suggests.

The last question marks discussed by the defence relate to whether the origin of certain objects is unclear, why certain pieces of metal were not examined, and – briefly summarised – what is meant by the observation that no indications were found of a relationship to an explosion. However, this information too can simply be found in the report.

Overall, the Public Prosecution Service concludes that there is no need to examine experts with regard to report Primo-4162.

Primo-08882 (marginal nos. 64-69)

That brings us to Primo-08882. This report concerns the investigation of fragments recovered from a number of pieces of wreckage. It was presented to the NFI on 25 September 2015 in the framework of a preliminary investigation.

Given that the activities concerned were performed as part of a preliminary investigation it is only logical that this investigation was aimed at selecting material for follow-up investigation. In the questions section on page 3, the following can be found:

‘In order to obtain a clearer picture of what pieces of evidence are to be analysed, an inventory of the steel fragments found in the pieces of wreckage is required. (...) Once the inventory is completed, an analysis can, subject to consultation, be conducted, whereby the following questions can be addressed.’

It is clear from the question’s formulation that ‘only’ a specific selection of fragments would be chosen for further analysis. When making that specific selection, account was taken of the findings of the previous investigation of recovered fragments (examining their size and elemental composition) and of the consultation held in January 2015, as is explained in the report. Before the court the defence described this consultation as an ‘expert meeting’, while in fact it was merely an intake discussion between the police and the NFI concerning the investigative material to be submitted and the questions to be formulated in this regard. In large, complex investigations it is customary for experts to be involved in the selection of the material to be examined and the proper formulation of questions, especially when many items of evidence are involved. That selection is intended to ensure the utility and quality of the investigation. The defence has characterised this consultation as an indication of contamination. In view of the above-mentioned reasons the Public Prosecution Service sees this differently.

The defence also sees the reference to findings from previous investigations as an indication of contamination. As the report clearly shows, in this specific preliminary investigation the findings of the previous investigation were involved only in the selection process. That is something different from the incorporation of those previous findings into the interpretation of the findings of the investigation that had yet to be performed.

The defence next describes two elements of the report as the ‘most striking question marks’.

The first concerns the observation in table 2 that five fragments were not examined and that no explanation was given for why they were not examined.

Table 2 does indeed state that five SIN numbers had ‘not yet been examined’. This is in keeping with the question put to the NFI, to the effect that first an inventory should be made of fragments found in the pieces of wreckage in order to ‘obtain a clearer picture of what pieces of evidence are to be analysed.’ The fragments were not submitted to the NFI with the instruction that the Institute should examine all of them. The instruction was first to draw up an inventory of the items in order to facilitate a selection of which fragments should be analysed.

The requested inventory was subsequently performed, as described in chapter 4 (‘Investigation’) of Primo-8882. The fragments were photographed and examined, inter alia, for the presence of characteristics specifically showing a relationship to an explosion, such as sooting, cracks and melted and warped surfaces. Investigators also looked for the presence of green paint, rusted irregularities and easily identifiable characteristics such as magnetism. After this preliminary examination, the fragments were investigated further only if there was a reason to do so. The report thus contains ample explanation of why some fragments were subjected to further investigation and others were not. If the defence believes there are specific reasons why a certain fragment was wrongly excluded from further examination, it can adduce those reasons. The fact that the defence has not done so leads us to conclude that it has no specific substantive questions or objections.

The next ‘striking’ element concerns a paragraph in which the expert explains that a large number of fragments consist (or are believed to consist) of unalloyed steel, and that these possibly came from the weapon that was used. Apparently it is unclear what is meant by ‘the weapon that was used’, and on the basis of what facts and circumstances the expert came to believe this.

Flight MH17 crashed on 14 July 2014. The Dutch Safety Board ruled out an accident or technical failure as the cause of the crash. That opinion is not disputed by the defence. The only remaining scenario is therefore that MH17 was downed by means of a weapon. The forensic investigation was aimed at establishing what type of weapon was used. The existence of uncertainty as to what type of weapon was involved does not mean that an expert is barred from stating that a weapon was used: it is obvious, after all, that a weapon was used. The phrase ‘the weapon that was used’ thus means nothing more and nothing less than the weapon with which flight MH17 was shot down.

The report offers clear insight into the facts and circumstances that formed the basis for the expert’s opinion that some fragments possibly came from the weapon that was used. I would again refer in this regard to chapter 4, which describes the anomalies the experts were alert to when conducting the inventory. When the inventory was made it emerged that some fragments displayed characteristics of an explosion. An aircraft does not generally contain fragments that display characteristics of an explosion, so it is neither strange nor confusing that an expert would qualify these fragments as ‘possibly from the weapon that was used’. The Public Prosecution Service therefore does not consider it necessary for the expert to provide further written or verbal explanation in this regard.

Taking all this into account, the Public Prosecution Service concludes that there is no need to examine an expert about report Primo-8882.

Primo-09126 (marginal nos. 70-88)

Between marginal numbers 70 and 88 the defence discusses Primo-09126, a report detailing the comparative analysis performed on the metal fragments found in the wreckage and one of the victims. The conclusion that the two authors of this report need to be questioned about ‘potential contamination’ rests on a number of inaccuracies.

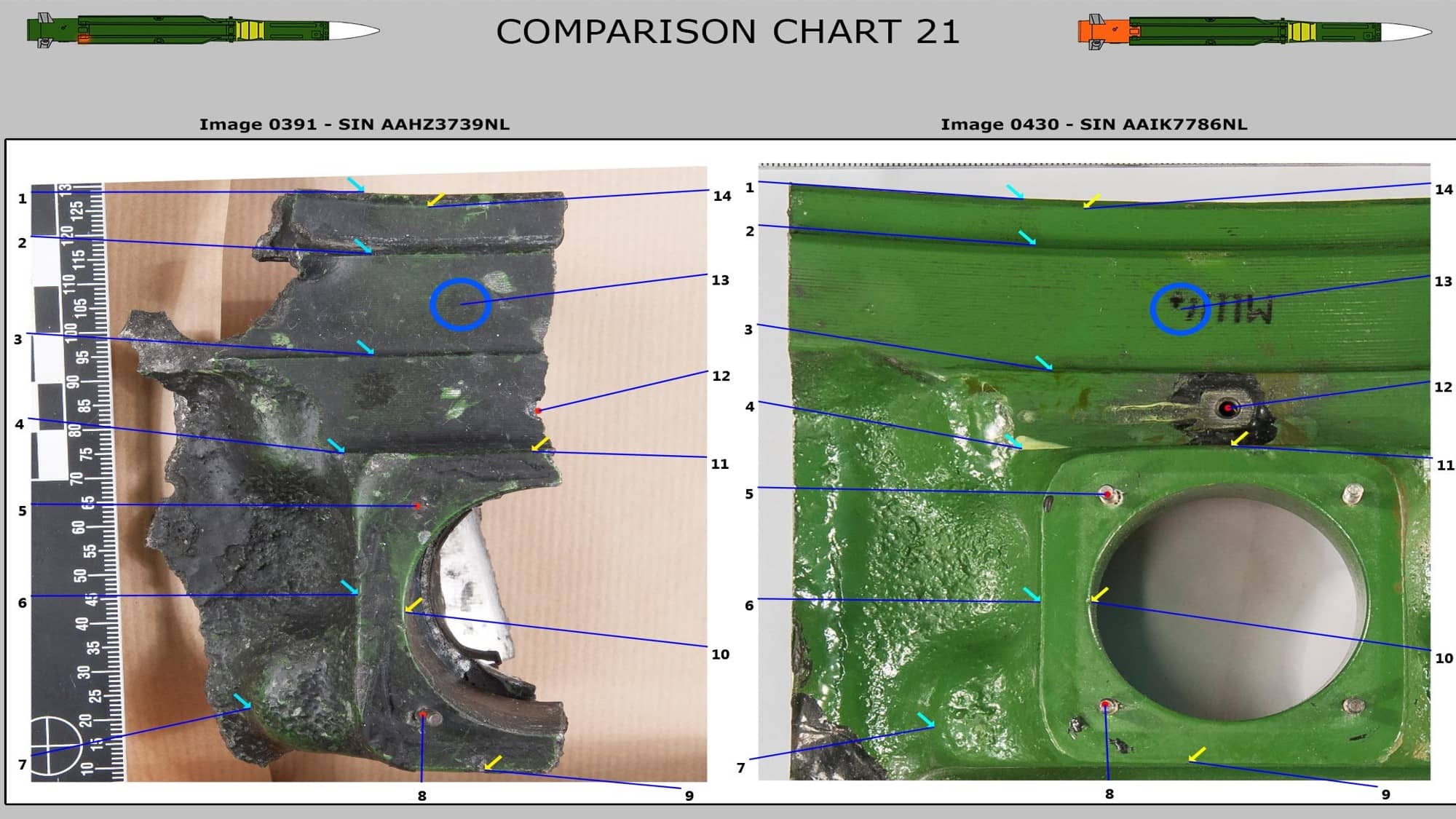

The report by the Australian Federal Police (AFP) cited in this document does not, as the defence contends, already contain the answer to the question posed by the NFI about a single specific fragment. The AFP compared the external characteristics of the fragment in question to reference material, while the comparison performed by the NFI was based on the elemental composition of that fragment and the reference material. In other words, the NFI employed a different type of analysis, as described in chapter 4 of its report. The AFP’s findings prompted the comparative analysis by the NFI, but nothing more than that.

The next point is that the analysis made use of an experimental method (marginal nos. 73 and 74). The defence seeks to assess the reliability of this method by examining the individuals that carried out this analysis. It is unclear exactly what questions it intends to ask.

The method in question, known as micro-computed tomography (microCT), is a technique whereby three-dimension black-and-white images can be created of relatively small objects. The grey-scale intensity in these images indicates the density of the material in the object. MicroCT makes it possible to identify the presence of other materials in the material being examined. In this case, the lump of metal from the frame of the cockpit window (SIN AAHZ3650NL) was analysed with the aid of microCT. According to that analysis the lump contained no material besides stainless steel.

Contrary to what the questions posed by the defence suggest, this was not the only analysis performed on the metal lump. After microCT analysis yielded no indications that would point to the presence of any other material or metals besides stainless steel, the elemental composition was also determined using a different, more common method. This method also showed that the lump was composed of stainless steel.

It was not the results of the microCT analysis that formed the basis for the further investigation but rather the results of the other analysis. In light of this, there can be no interest in a further examination of witnesses with regard to microCT analysis because this would have no influence on the conclusions that can or cannot be drawn from the forensic investigation as a whole.

The defence would also like the examine the authors of the report about the Bayesian approach used (marginal no. 77). However, this is a question dealing with general information about the NFI’s standard working methods, As such, it does not warrant the examination of an expert by the examining magistrate. The defence can readily obtain such information from public sources. In the report itself the experts refer to an appended document containing terminology from the field of probability used by the NFI, which can also be found on the NFI’s website. The NFI offers an online course on this subject which is open to members of the public. Since the court is accustomed to interpreting reports in which results are presented in this manner, there is no need to examine experts about this subject for any decision it must render.

What remains of the grounds for this request is a hard-to-follow argument which reads like an advance statement of the defendant’s case crossed with a misreading of the report.

For example, the defence speaks about ‘findings that were set aside’ and discounted hypotheses (marginal nos. 82 and 87), while the report says nothing of the kind.

Taking all this into account, the Public Prosecution Service concludes that, on the basis of the explanation offered by the defence, there is no need to examine experts about the Primo-9162 report.

Other reports (marginal nos. 89-95)

Pulatov wishes to examine various experts about the reports summarised in appendix 3. Inthis connection, it provides no reasoned indication of what questions still need to be addressed because this would take ‘an unreasonable amount of time’ (marginal no. 90). At the same time they do announce that the examination of these experts should take several days per person (marginal no. 92). As we already stated in our introduction, such a request cannot be granted. In order to conclude that it is important or necessary to examine a particular expert, it must be acknowledged that there are relevant questions to be answered. This is not possible without providing concrete grounds for the request. The defence has had so much time to submit its requests for further investigation that the lack of concrete grounds is unjustifiable. If the defence was concerned about using up too much time during the hearings, it obviously could have put its reasoning in writing and simply summarised it in court.

The current request must therefore be denied due to insufficient grounds.

Primo-06556 (marginal nos. 96-98)

The defence also has questions about Primo-06556, a report containing the findings related to the analysis of a number of fragments recovered in Wijk bij Duurstede. This analysis sought to determine a possible relationship between these fragments and an explosion inside or outside the aircraft. The defence would like to examine the experts who performed this analysis about two specific fragments. One is a small piece of reddish brown steel, which was found melted in a piece of underwear. The underwear in question was found scattered among the luggage and other personal property; it was not being worn by one of the victims. The underwear arrived in the Netherlands on 21 October 2014, meaning that it had lain out in a war zone for several months. During that period there was active fighting between the Ukrainian armed forces and separatists. The report noted that the fragment could have originated from a weapon that was used in hostilities in the area where flight MH17 came down. The other fragment was also found amid the luggage and other personal property. It does not contain any characteristics indicative of an explosion, or any residue of explosive substances. The elemental composition does not match fragments recovered from the victims’ bodies. The questions raised by the defence are insufficiently clear or relevant to justify calling a witness. It is only natural that we would be unable to pinpoint the origin of every single fragment found at the crash site. In so far as the defence believes that these two fragments, which were found amid luggage exhibiting severe fire damage, could cast a different light on the weapon used, it is free to ask the experts who have yet to be examined about the pattern of damage.

Thus, it is not necessary to examine the authors of Primo-6556.

Primo-08139 (marginal nos. 99-108)

This brings us to Pulatov’s requests about Primo-8139, a provisional report from 2016 about the investigation into traces of explosives on the wreckage of MH17. Here, too, the defence has formulated its questions as if this report were a stand-alone document, whereas it is a provisional report that was replaced by a final report at a later date: Primo-8688. This fact alone shows that the reasoning offered in support of this request is inadequate.

The results of the investigation into traces of explosives on the wreckage are described in clear language, as are the limitations that make it impossible to attach more specific conclusions to these findings. These limitations mainly relate to the long period of time that the wreckage was sitting in a war zone and the way in which it was gathered and transported. The Public Prosecution Service does not understand why the defence would dismiss these limitations as ‘speculation’, let alone why that these ‘speculations’ would constitute grounds for examining a witness.

The defence also takes the position that the investigation was incomplete because the detonator of the warhead was not examined. This could have shown whether the detonator contained PETN. The defence wishes to question the expert about this. The defence fails to appreciate that such an examination is of no value: the presence or absence of PETN has no bearing on the limitations on the investigation into the wreckage, i.e. the fact that it was left outside in a war zone for a long period of time and the manner in which it was collected and transported. The defence neglects to explain in concrete terms what meaningful investigation was wrongly overlooked and what effect that might have had.

This request should also be denied, due to insufficient justification and relevance.

Addition of report 111 to the case file (marginal no. 104)

Pulatov asks the court to add NFI report 111, on traces of missile fuel, to the case file.

We have no objection to this.

Primo-07626 (marginal nos. 109-118)

In addition, Pulatov has questions about the report on the physical comparison of recovered foreign material to material from the two reference missiles. To that end, he wishes to examine the author of this report, a forensic investigator from the Australian Federal Police about his ‘expertise or lack thereof’ (marginal no. 113), the ‘limitations to his investigation’ (marginal no. 113) and the way in which he conducted the investigation (marginal nos. 114 and 115).

Here once again the defence raises objections to the report without making clear what additional information it wishes to learn from the witness concerned. There is no need for this forensic investigator to reaffirm that he is not an expert on Buk missiles. The police officer in question has already been quite clear about this point. This is also irrelevant since he is not making a technical judgment about a weapon. He confines himself to comparing the external characteristics and magnetic qualities of the objects found to parts of a Buk missile. The similarities he found are carefully described. All the questions posed by the defence about his ‘expertise or lack thereof’ are already answered in his report. The same applies to the fact that his reference material consisted of two different types of Buk missile. Further questions from the defence about this ‘limitation’ cannot be answered by this investigator. Moreover, the observation that there is a ‘limitation’ in this instance implies that the findings depend on which 9M38 missile and which 9M38M1 missile were involved in the comparison. Yet the documentation provided by the Russian Federation about the assembly process for such missiles makes it clear that this makes no difference whatsoever.

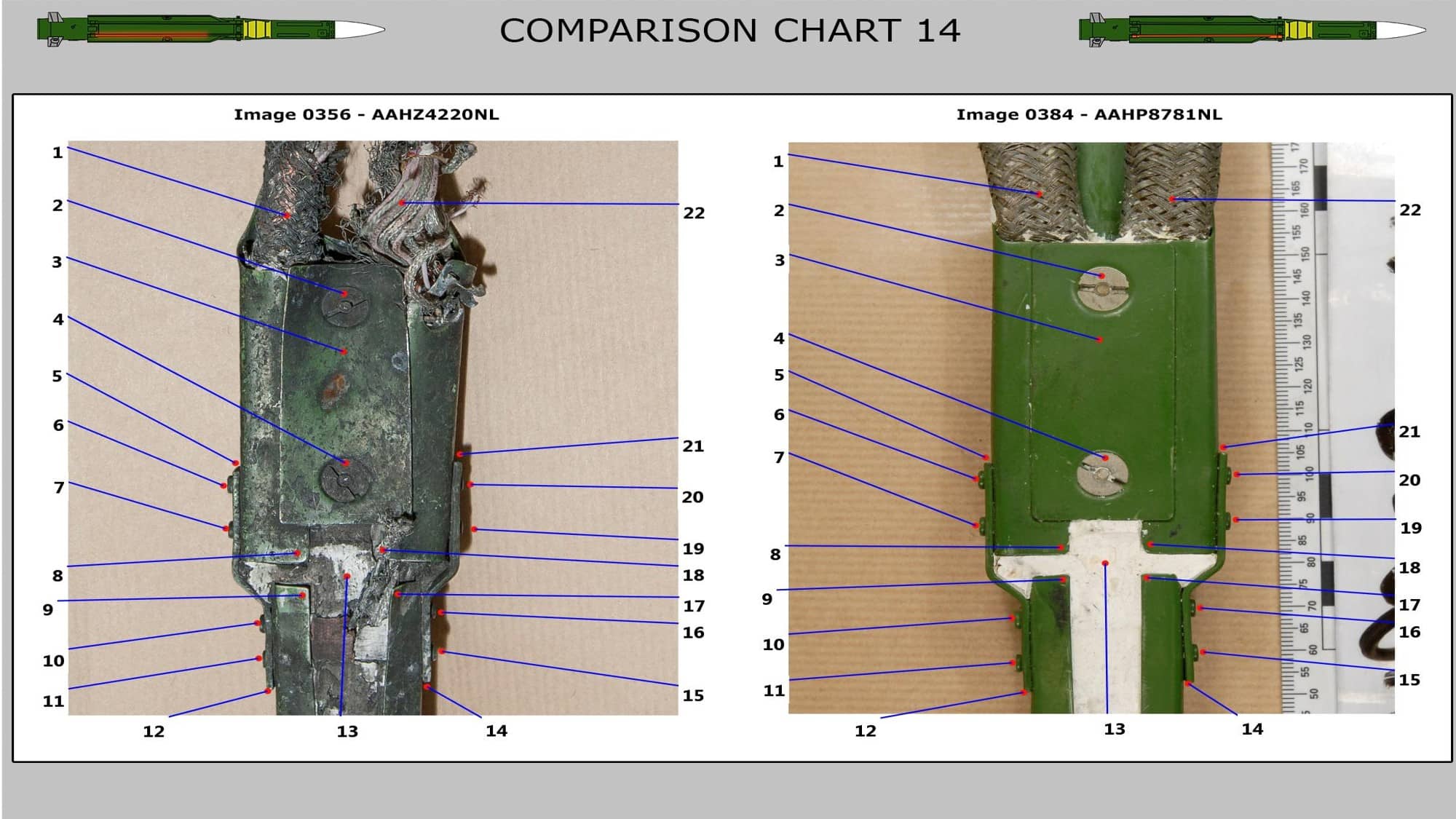

This leaves us with the questions raised by the defence about the way in which this expert performed his work. This was a straightforward comparison of the external characteristics and magnetic qualities of the material. This comparison was described in detail in the report, which also includes photographs. A total of 475 photos from this analysis were included in the case file. In combination with the in-depth report, they offer a detailed picture of the investigation and its findings. On 7 October we drew the defence’s attention to these photos.

The way in which this investigator performed his work is apparent not only from these and hundreds of other photos; it was also explained in detail in the text. Even so, the defence contends that it is ‘unclear’ whether ‘the reference material was physically present during the investigation and/or whether photographs of it were also examined’ and ‘whether a microscope or other devices were used’ (marginal no. 115). Those questions are all answered in the report and the photos: the metal lump, the other pieces of evidence and the reference material were physically examined and compared by the forensic specialist. In both Ukraine and the Netherlands, he took part in the examination of these missiles and other pieces of evidence. He continued this work in Australia on the basis of photos and 3D scans made by the Expert Team on Visualisation and Reconstruction (ETVR).

Pulatov also wishes to question this investigator about the direction of the impact (marginal nos. 116-117) and the location where the missile detonated (marginal nos. 117). The first question is answered in the report: on the basis of photos taken earlier (i.e. before the lump was removed from the window frame), the investigator described and explained in detail the general direction from which the lump must have entered the frame. This is a reasoned observation that the defence can assess for itself on the basis of the photos. According the defence, the question about the location of the detonation lies outside this investigator’s area of expertise (marginal no. 117), meaning that there is no reason to ask it.

Finally, Pulatov wishes to question the investigator about his conclusion that the ‘features’ of a foreign fragment (AAGK3338NL) ‘are consistent with the umbilical slide cover of both the 9M38 and 9M38M1 reference missiles’ (marginal no. 118). This, too, the defence alleges, is unclear. If we examine the report, we can see that the investigator describes his findings over the course of nearly four pages. These findings are further ‘illuminated’ by no fewer than 65 photos. On the basis of that detailed description and the attached photos, it is clear what ‘features’ the investigator’s conclusion is based on. Pulatov can object all he wants, but the photos tell the whole story. If the defence has reached a different conclusion from the investigator on this matter, it is free to inform the court. No one has to be examined for that purpose.

Primo-06937 (marginal nos. 119-124)

The next request relates to Primo-06937, the official report explaining how the aforementioned ‘lump’ was removed from the cockpit window frame. The defence wishes to ask questions about how the lump was found in the window frame, and in particular about the direction of the impact. It also raises the question of whether the researchers at the TNO, RMA, NLR and NFI endorse the findings of the reporting officers about the direction of the impact. To begin with the latter question: this is a question that the reporting officers are in no position to answer. A reporting officer cannot be asked about somebody else’s opinion. Nor have the organisations mentioned had a chance to form an opinion about the reporting officers’ findings. If the defence believes that these matters should be investigated further, it must first offer a concrete explanation of what the added value would be. The mere fact that reporting officers are not scientists is in any case insufficiently specific to presume such added value.

The first question, about the findings of the reporting officers themselves with respect to the lump of metal found in the cockpit window frame, is already answered in the official report. That report contains not only a factual description of what the reporting officers did and observed, but also 14 photos, which show the reader what the reporting officers are describing. The media file contains these and other photos in a higher resolution.

At the hearings in June we already discussed this official report in detail, and at that time we also showed some of the photos. We will now show three photos, two of which were shown in June:

In this photo we have zoomed in on the part of the cockpit window frame where the lump was found. The lump itself is not visible, but you can see the undisturbed soot on the frame, as described in the official reports, which can mainly be seen in the brownish yellow section under the two parts of the frame. You can also see a crack in that brownish yellow piece.

In the next two photos you can see that, as described in the official report, other material in the frame had to be cut away to reach the lump. One of the two sections of the window frame was completely removed, thereby revealing the underlying brownish yellow part and making it easier to see the aforementioned crack. Once a final piece of the section was cut away, the lump then became visible, at the exact place where the crack was.

There are many more of these kinds of photos in the case file, but these three are sufficient to demonstrate that the defence is seeking to ask questions about a small element of an investigation which is documented in such meticulous detail, in writing and in photographs, that every relevant aspect of it can already be found in the case file, in text and images.

If Pulatov has further questions about this specific damage, he can, of course, pose them to the experts who are already scheduled to testify about the pattern of damage. We do not see how an examination of the authors of Primo-6937 can add anything essential to their official report or the expert testimony that is already scheduled to take place. There is also the question of why this request was not submitted until now, in November, when this official report and the findings it contains were discussed at length in the hearing back in June.

Investigation by the NLR, the RMA and TNO

The defence has requested the examination of the report authors from the Netherlands Aerospace Centre (NLR) (marginal nos. 160-167), the Belgian Royal Military Academy (RMA) (marginal nos.140-159) and the Netherlands Organisation for Applied Scientific Research (TNO) (marginal nos. 168-186).

In part, these requests relate to investigative work that was done at the behest of the Dutch Safety Board (OVV). This involved an examination of the pattern of damage to flight MH17, performed by external experts from TNO and the NLR.

As the defence itself has noted, this raises questions about the possibility of using the Dutch Safety Board’s final report and external reports by TNO and the NLR as evidence. Now that concrete requests have been made, those questions can be answered directly.

Under section 69 of the Kingdom Act establishing the Dutch Safety Board (ROVV) certain sources of information used in OVV investigations may not be used as evidence in a criminal case. The purpose of this principle is to prevent information gathered by the OVV from being used against the individuals concerned, for example in a criminal case. This ensures that those concerned can share information freely, without fear of being held legally liable, and the OVV can thus collect as much data as possible for its investigations.

Because such information from these parties may also be incorporated in the OVV’s final report, it was ultimately decided, following a parliamentary debate, to exclude the entire report from the evidence (section 69, subsection 1(f) ROVV). Consequently, the OVV report cannot be used as incriminating evidence against Pulatov and the other three defendants. The report can, however, be used as exculpatory evidence or to aid the court in assessing the completeness of the criminal investigation and any opportunities for further investigation. This is why the Public Prosecution Service added this report to the case file: so as to provide the most complete possible picture of the available information concerning the crash of MH17. It was for this same reason that, during its explanation of the criminal investigation, the Public Prosecution Service referred to the OVV’s findings about the sound waves picked up by the CVR, as these findings were in line with all the findings from the criminal investigation, which made it possible to rule out the possibility of both an explosion from inside the aircraft and an attack by a fighter aircraft. In light of that, no further investigation of the sound waves on the CVR was necessary because the OVV’s findings on that subject matched the findings that emerged in the course of the criminal investigation conducted by the Public Prosecution Service. The Public Prosecution Service has not cited the OVV investigation to serve as incriminating evidence, but rather to clarify its conclusion that no further investigation needs to be conducted on this point.

It is thus clear that the final report cannot be used as incriminating evidence.

Where the external reports by TNO and the NLR are concerned, this is less straightforward. According to the letter of the law, the reports are not documents that have been drawn up or approved by the Board within the meaning of section 69, subsection 1(f) of the Kingdom Act establishing the Dutch Safety Board, but by external experts, which were then released separately by the OVV. Moreover, the reports deal with the examination of pieces of wreckage which were also seized by the authorities in connection with the criminal investigation. The use of those technical findings in a criminal case does not jeopardise witnesses’ willingness to cooperate in an OVV investigation. Those pieces of wreckage are, as it were, silent witnesses, which automatically yield up the information they contain, not human beings who refuse to speak because they could subsequently be drawn into legal proceedings.

The legislative history is not clear-cut with respect to the interpretation of this statutory provision and the question of whether or not external reports appended to an OVV report can be used as evidence.

Be that as it may, it is the position of the Public Prosecution Service that reports about the pattern of damage commissioned by the OVV and drawn up by the NLR and TNO add nothing to the findings that were established in the criminal investigation. As far as the Public Prosecution Service is concerned, reports commissioned by the OVV are not expected to be used in evidence. For that reason, we do not see the need for or importance of examining the reports’ authors. In any case, in the explanation offered by the defence, we find no subjects for examination that could potentially shed a new or different light on the existing findings of the criminal investigation. To the extent that the defence has relevant questions about the NLR’s examination of the pattern of damage in the criminal investigation, it can put them to the expert of NLR in the ongoing investigation being conducted by the examining magistrate.

The ongoing investigation by the examining magistrate